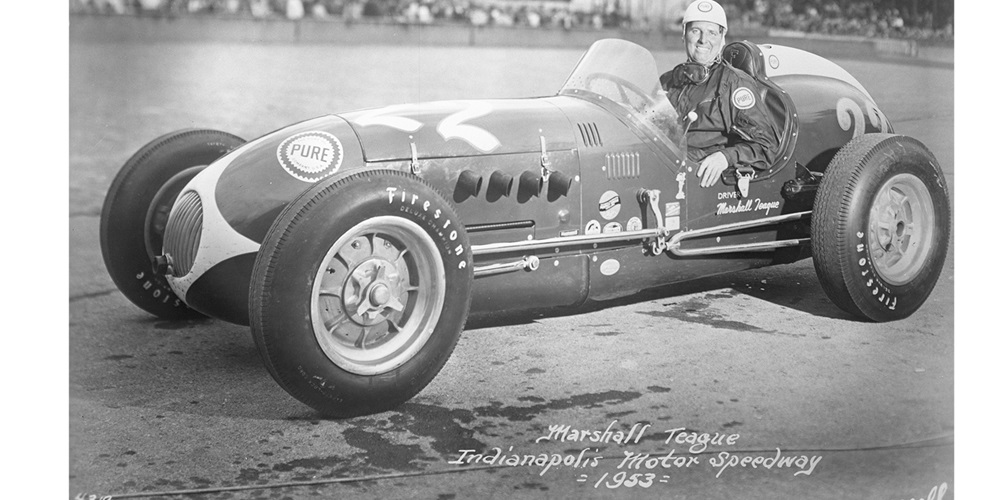

On May 30, 1953, early NASCAR standout and lifelong Daytona Beach resident Marshall Teague finally was able to achieve his longtime ambition of driving in the Indianapolis 500. But there had been a hefty price to pay.

There was, at the time, no international exchange of drivers for major events, and the only way somebody could compete in such a contest was to take out a license with the organization sanctioning it, which more than likely would result in some sort of disciplinary action from the one to which the driver normally belonged.

The portly Teague – by all accounts, one of the nicest people ever to don a helmet – made the very difficult decision to join AAA (the "500's" sanctioning body) for 1952, knowing that any attempt to rejoin NASCAR in the future likely would require the posting of a hefty bond. He had, in fact, been with NASCAR since its very beginnings. When Bill France called the historic meeting Dec. 14, 1947 at the Streamline Hotel in Daytona Beach, out of which NASCAR was born, Teague was one of 35 people in attendance. Not only that, but he came out of the meeting as the organization's first treasurer.

So, having joined AAA for 1952, was Teague now cleared to go directly to the Indianapolis Motor Speedway? Not exactly. First, he had to prove his allegiance to AAA by racing with that organization for a full season, which he did, piloting his all-conquering Hudson Hornet to the 1952 AAA stock car title. He finally made it to the Speedway the following May, ran as high as third in the "500," and was still holding onto fifth when an oil leak sidelined him with 30 laps to go.

The following year, a longtime Teague colleague, Frank "Rebel" Mundy (real name Francisco Eduardo Melendez), appeared at Indianapolis under almost identical circumstances. The colorful Mundy had given up NASCAR for 1953, racing AAA stocks for a year and succeeding Teague as the champion before being accepted at IMS. But he was not able to qualify for the 1954 “500.”

By 1958, things had relaxed a little. AAA had been replaced by the United States Auto Club (USAC), and former AMA motorcycle champion-turned-NASCAR stock car driver Paul Goldsmith was able to go straight to Indianapolis, doing so with a Kurtis/Offy roadster recently purchased by his NASCAR partner, Henry "Smokey" Yunick. In February, Goldsmith had won the very last of the NASCAR classic "grand nationals" over Daytona's beach course, driving a Yunick Pontiac.

But it was still necessary to join USAC to compete in the "500," and Smokey Yunick – even as an owner and mechanic – was to have plenty of his own licensing issues with both sanctioning bodies over the next couple of years.

Several car owners in 1960 and 1961 dearly wanted to hire Glenn "Fireball" Roberts for the "500," most notably Al Dean of the Dean Van Lines team. But poor Roberts had to decline. As much as he wanted to accept, he could not risk joining USAC and giving up running the balance of the season with NASCAR.

In the meantime, an organization called the Automobile Competition Committee for the United States, better known as ACCUS, had been formed. Numerous sanctioning bodies throughout the world belonged to the Paris-based Federation Internationale de L'Automobile (FIA, the worldwide governing body), but almost exclusively, membership would consist of only one sanctioning body per country. Because the United States had several, it was decided to form ACCUS for the purpose of representing all of them with one set of delegates.

One main advantage to this move was that it opened the doors for the interchange of drivers in selected major international and national events so that a "graded" NASCAR or Sports Car Club of America (SCCA) driver was free to enter a designated major USAC race (such as the "500") as a virtual guest. By the same token, USAC drivers could enter the Daytona 500 or the Firecracker 400, or a major SCCA road racing event at Riverside, California, for instance, without having to join the hosting sanctioning body and risk being disciplined by their own.

The plan did not go particularly smoothly at first – especially when some drivers would want to compete in another sanctioning body's event on the same day as one of their own – but by 1963, everything had pretty much been worked out. Junior Johnson showed up at Indianapolis with his NASCAR and FIA licenses and took part of a "rookie" test. Curtis "Pops" Turner also was there, but as a USAC member. He had fallen out of favor with NASCAR and had been handed a "life" suspension. (It ended up lasting about three years.) Also on hand and trying to land a car to drive were 1961 Atlanta 500 winner Bob Burdick and the recent Daytona 500 winner, DeWayne "Tiny" Lund. Burdick never was able to connect, but with the help of Parnelli Jones, Lund got a car – Doug Stearly's – only to have to decline when his 6-foot-5, 270-pound frame would not fit into the cockpit.

In the years that followed, however, a number of NASCAR standouts took advantage of the prevailing situation and headed to IMS to at least give it a try.

In 1953, Teague qualified 22nd at an average speed of 135.721 mph and climbed as high as third before settling into a steady fifth. That is where he was running when an oil leak ended his run after 169 laps. Teague drove several famous cars in practice during the next few years, including a Novi and the Sumar "streamliner" in 1956, but his only other start came in 1957, when he finished seventh. He did take part in the 1954 race as a relief driver for both Duane Carter and Gene Hartley.

By far the most rewarding "500" run for Teague came in 1957, when he drove a Sumar Special to a seventh-place finish. Sumar was a speed equipment company in Terre Haute, Indiana, which got its name from the first couple of letters of the first names of the wives of its two owners. The wife of Chapman Root was Susan, and the wife of Don Smith was Mary.

When former motorcycle racing standout Paul Goldsmith left NASCAR to come to the Speedway in 1958, he stepped into an open-cockpit, open-wheel car for the very first time in his life. Remarkably, during his entire career, he had only eight total starts in open-wheel cars, all of them being USAC National Championship races, and six of those being the Indianapolis 500! His initial start in Smokey Yunick's ex-Lee Elkins, Andy Linden-driven Kurtis/Offy (fifth in 1957) lasted only three-quarters of a lap before he became involved in the multi-car accident in which the beloved Pat O'Connor lost his life. Jerry Unser, who vaulted the outer wall on his way to sustaining a dislocated shoulder in that accident, left tire marks on Goldsmith's uniform and helmet. Goldsmith came back to finish fifth in 1959 and third in 1960, driving for Norman Demler with Ray Nichels as his chief mechanic.

With the colorful Curtis "Pops" Turner serving a "life" suspension from NASCAR (which would last about three years), he decided to head north midway through the 1962 season and run USAC. In addition to competing in several stock car races, he tried, unsuccessfully, to qualify the Dean Van Lines dirt car in August at Springfield, Illinois. The following April, he placed 12th with another dirt car on the paved 1-mile oval at Trenton, New Jersey, and then showed up at the Speedway with a revolutionary car Yunick had built the year before for Jim Rathmann. The 1960 winner had not found the car to his liking, and Turner also struggled. He made it through his rookie test but crashed without making a qualifying attempt. He finished out the season in USAC stock cars, winning two races and finishing fourth in points behind Don White, A.J. Foyt and Norm Nelson. However, it wasn't long before he was back with NASCAR.

It may come as a surprise to many to learn that race fan favorite Ralph Liguori, who never was able to earn a "500" starting position despite several years of trying, spent a few years as a NASCAR driver. He drove in the Southern 500 at Darlington five times and placed in the top 25 in points for four straight seasons (1952-55), peaking with a 10th-place finish in 1954.

Robert Glenn "Junior" Johnson, immortalized by author Tom Wolfe in his memorable work "The Last American Hero," was part of the first wave of NASCAR drivers to come to Indianapolis once it was no longer necessary to renounce that organization and join USAC. The car in which the hefty Junior took part of his "rookie" test sported a roll cage and is believed to have been the very last Indianapolis car ever built by Frank Kurtis. Junior left town, typically, without having had a whole lot to say.

Perhaps the strangest car ever entered in the "500" was Yunick's "sidecar" in 1964. It was also somewhat of a surprise to learn how passionate driver Bobby Johns was about driving at Indianapolis. He actually had visited the track as a teenager in the summer of either 1948 or 1949 when his father, Socrates "Shorty" Johns, had come up to the Midwest for a summer of midget car racing. Bobby was his "stooge." He also told the story of 1949 "500" winner Bill Holland's famous suspension for competing in a late-season 1950 event not sanctioned by AAA, Bobby revealing that the event was a match race in which he was the other driver.

"When Smokey invited me to go up to run the 'sidecar' at Indianapolis in 1964," Bobby Johns said, "I went straight to the airport. I took nothing with me. Not even a toothbrush. I wanted to get up there as quick as I could before somebody else got that ride."

The famed Wood Brothers of NASCAR were brought in by Ford Motor Company in 1965 to perform the pit stops for the Ford-backed English Lotus team. In addition to doing so for winner Jim Clark, they also serviced Clark's teammate, Johns.

While the hiring of Johns may have raised a few eyebrows and could have been interpreted as having been engineered by Ford, Johns later revealed that he had become friendly with the Lotus boys the year before when Yunick's "sidecar" occupied the garage next to theirs. Not only was Colin Chapman more than satisfied with Johns’ seventh-place finish, he invited Johns to partner Clark again in 1966, an invitation he had to decline. Johns was the first NASCAR driver to start in a "500" without having had to join USAC.

Freddie Lorenzen likely would have made an excellent "500" driver if he chose that route. Lorenzen, from Elmhurst, Illinois, won the USAC Stock Car championship in 1958 and 1959 while still in his early 20s. He then suddenly headed south and became a giant in NASCAR with Holman & Moody Fords. He usually visited the Speedway during practice each May, and in November 1965, he accepted the invitation of car owner George R. Bryant to take a few laps in a rear-engine car at IMS. George Salih, who built the famous "laydown" with which Sam Hanks and Jimmy Bryan won the "500" in 1957 and 1958, respectively, was the co-chief mechanic along with Howard Gilbert. Lorenzen enjoyed the experience, but an entry in the "500" never materialized.

LeeRoy Yarbrough adapted to the Speedway much better than his finishing positions would indicate. He made seven appearances at Indianapolis but qualified only three times and never finished, though he always ran hard. But for a last-minute driver switch while sitting in the qualifying line in 1968, Yarbrough would have driven the third STP Lotus "wedge" turbine instead of Art Pollard. He arrived in 1971, having just finished third at Trenton, driving for Dan Gurney, but an accident sidelined him before qualifications began.

By far the best finishes by a visiting NASCAR driver were by Donnie Allison, winning Rookie of the Year honors after coming in fourth in 1970 and finishing sixth in 1971. He drove for Foyt in both years, these being his only two appearances. As soon as the 1971 "500" was over, Allison flew to Charlotte, North Carolina, where he finished second to brother Bobby Allison in the World 600 the following day. He then hopped onto another plane and flew back to Indianapolis, where he appeared at the victory banquet that same night.

Cale Yarborough made four appearances at Indianapolis, in 1966, 1967, 1971 and 1972. His best finish was 10th in 1972, the second year in which he was on the Gene White team with Lloyd Ruby. One of his memories of Indianapolis was getting stuck in traffic on the morning of the first qualifying day in 1966, parking his car at the side of the road and walking briskly to the track.

Charlie Glotzbach, who had finished second to Yarbrough in the 1969 Daytona 500, came to the Speedway that May to drive a stock-block Chevrolet for Gene White. "Charging" Charlie was a Hoosier, having been born in Lanesville and raised in Georgetown. He passed his rookie test but never went to the qualifying line. He had a second and final try in 1970 with a turbocharged Offy-powered Eagle but did not make an attempt with that one either. In 1972, he was runner-up at Daytona again, this time behind Foyt.

Although Bobby Allison was from Hueytown, Alabama, as a teenager he attended several races at the Milwaukee Mile while spending the summer with an aunt. Based on the success of brother Donnie at the Speedway in 1970 and 1971, Bobby was more than happy to accept Roger Penske's offer of a "500" ride in 1973.

He was teammate to Gary Bettenhausen and defending winner Mark Donohue. It was a trouble-plagued and tragedy-filled year, and while Bobby did qualify 12th, his race was over almost before it began. On the third and final day of a rain-delayed marathon, he had a connecting rod fail on only his second lap. He ran well two years later, and was within the top 10 for much of the way until a gearbox failed after 112 laps. He led Lap 24 during pit stop shuffles.

Neil Bonnett, whose deadpan dry wit was absolutely priceless, was briefly Roger McCluskey's teammate at Indianapolis in 1979. With his NASCAR career having momentarily stumbled, he signed on in the spring to drive a turbocharged AMC-powered car for Warner W. Hodgdon.

In the meantime, Bonnett had unexpectedly hooked up with the Wood Brothers, so the plan was for him to qualify at Dover on Friday, return to Indianapolis for the third day of qualifying on Saturday, and then go back to Dover for the 500-lap marathon on Sunday. When rain at Dover pushed qualifying to Saturday, Jerry Sneva jumped into Hodgdon's car at Indianapolis and qualified it. Bonnett stayed in Dover and won the race, and the following week Jerry Sneva drove the Hodgdon car in the "500."