The original major auto races in the United States were conducted on long courses using public roads. The first of these was the Vanderbilt Cup with its inaugural edition on October 8, 1904. Commissioned by William K. Vanderbilt, Jr., the millionaire scion of America’s richest family, the event immediately ranked among the biggest in the country. By 1906 even conservative estimates stated that over 200,000 people attended the contest.

The course for the first Vanderbilt Cup was 30.4 miles of crushed stone and dirt roads slicing through Long Island, New York countryside. Even though these roads were atrocious by today’s standards, they were, unlike 1-mile horse tracks, deemed long enough in stretches to test the power and durability of engines.

The Vanderbilt Cup’s success encouraged similar events. Among the best known were the American Grand Prize in Savannah, Georgia and races at Fairmont Park in Philadelphia. Both attracted huge crowds, with Fairmont Park promoters claiming an attendance of 400,000.

In some ways, these massive gatherings were more of a problem than opportunity. Very few purchased tickets, simply securing locations roadside. Not only did the races tie up public thoroughfares, but the crowds were nearly impossible to control, wandering onto the course in the middle of the race. The Vanderbilt Cup was forced out of Long Island after deaths and injuries to competitors and spectators in 1910.

None of this escaped the observant mind of the entrepreneurial Carl Fisher, the leader among the four founders of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway and the track’s first president. As early as 1903, Fisher considered the development of a large speedway to give American manufacturers a quality facility to test automobiles.

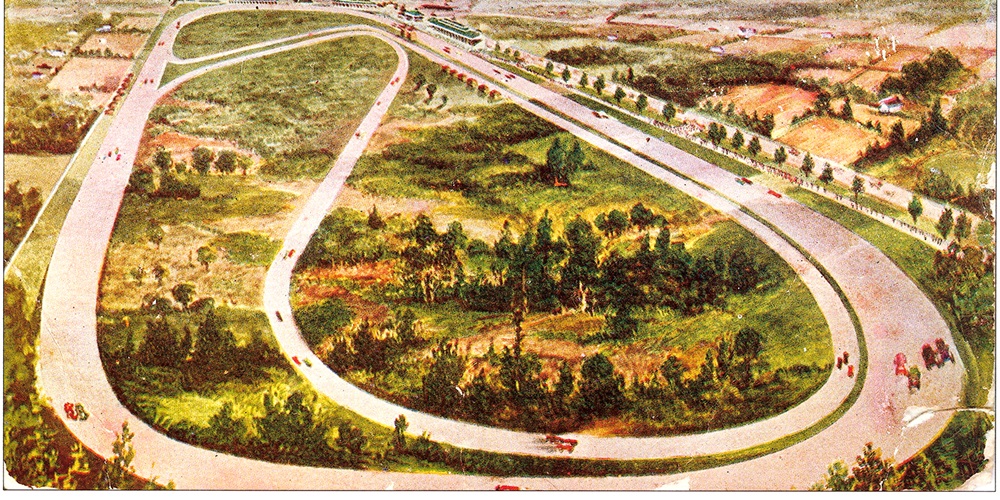

Fisher’s vision – at this time little more than a rough sketch on a restaurant tablecloth – was of a 3-mile oval augmented by an additional 2 miles of twists and turns in the center. Under this scenario, cars exited the oval to run the distance of the 2-mile road course and then returned to the outer circuit. The combination would create a 5-mile course. There is evidence hosting the Vanderbilt Cup was on Fisher’s mind as he made a bid to stage the legendary race on the oval in 1915 - well after abandoning his dream of a road course.

It wasn’t until March 20, 1909 that the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Company was incorporated. By that time Fisher’s tablecloth sketch had evolved. P.T. Andrews, a New York engineer hired as the Speedway’s superintendent of construction, quickly assessed the dimensions of the grounds and the proposed track.

The challenge was squeezing the track into the 320 acres that became the Speedway grounds. Using a scale cardboard model of the four quarter-mile corners and then drawing varying distances for both the long and short stretches, Andrews illustrated to the founders how a 2.5-mile oval would allow room for additional grandstands as the Speedway grew.

To preserve Fisher’s dream of a 5-mile circuit, Andrews extended the infield road course to 2.5-miles. The founders approved, and the King Brothers of Montezuma began work grading the land into the configuration of the oval that exists today - including the 9-degree, 12-minute corner banking.

Work was slow and arduous. Initial development on the road course began, but was soon set aside to focus on the oval as a commitment to the Federation of American Motorcyclists (FAM) for a championship race meet drew closer. Most of the facility was ready ahead of the deadline, including 41 white-with-green-trim buildings as well as 3,000 hitching posts for fans arriving by horse. Problems, however, soon emerged.

The issue was smoothing the running surface, which was composed of crushed stone and asphalt gum. An excellent surface when compared to typically unpaved, craggy public roads; the track would obviously be rough going for high speed racing. The other issue was spanning a creek that ran under the southwest corner of the oval.

Fisher and his team, sometimes working around the clock, nearly accomplished the impossible: the construction of a world-class racing facility from undeveloped land in four months. They came close, but fell short of providing a suitable racing surface.

In the days leading up to the Aug. 13-14 race meet, motorcycle riders approached the treacherous track with trepidation. There was good reason.

The race meet, scheduled as a two-day affair, was curtailed after a single day when Indian rider Jake DeRosier was severely injured when his front tire exploded on the track’s piercing stones. An auto race meet held just four days later yielded even more devastating results with five deaths attributable to poor track conditions.

Throughout this time the local newspapers referred to the Speedway as a 5-mile track even though only the oval was in use. Those references quickly stopped as Speedway management turned away from their vision of including a road course in the facility and poured their resources into producing the world’s safest racing venue by paving the oval with 3.2 million bricks.

Fast forward to Dec. 2, 1998 as the Speedway announced plans to host the United States Grand Prix Formula One race. Construction on a 2.606-mile, 13-turn road course began immediately. Like the 1909 layout, the road course utilized a portion of the oval to complete its circuit.

The job, however, extended far beyond the running surface. In addition to the new course dimensions, 36 Formula One-style pit-side garages and a new “Pagoda” control center architecturally inspired by the previous control tower and the wooden Pagodas of the past were erected.

These were just two of the larger changes beyond the course. A giant racing facility with more than 90 years of history accumulates a lot of infrastructure. Acres of buildings and grandstands needed to be modified or demolished. A total transformation behind the established pit area was required to accommodate new offices, media facilities, new pit lanes and much more.

A key figure in making all this come together was Kevin Forbes, the Speedway’s director of engineering. At the direction of then Speedway president and CEO Tony George, Forbes developed a plan for the changes as early as 1991. George, only a year into the job at that time, clearly had a vision to bring Formula One to the Speedway.

“When I first thought about it, I saw the ultimate dilemma,” Forbes says. “I knew it would be an engineer’s dream to become involved in such a complex, interesting and historically important project while at the same time I envisioned the potential for my worst nightmare.”

The job was complex enough, but the extensive team of architects, engineers and construction craftsmen had to organize their project so they did nothing to disrupt two of the biggest sporting events in the world: the Indianapolis 500 and NASCAR’s Brickyard 400. The Herculean effort was worthy of the Racing Capital of the World. Eight Formula One races were conducted from 2000 to 2007 and were succeeded by another world-class event in 2008, MotoGP.

Although nowhere near the complexity of the original road course transformation, significant modifications were required to accommodate the world’s fastest motorcycles. The MotoGP course had 16 turns and was 2.605-miles long. A major consideration was the run-off areas for safety. This is because, according to Forbes, the rule-of-thumb is that motorcycles require twice as much run-off area as do the Formula One cars.

Much of this concern was addressed by creating four additional corners inside turn one of the oval; taking that high-speed portion of the course out of the equation. This design was made possible by running the motorcycles counterclockwise, the opposite of Formula One.

Part of the engineering of this solution required an accommodation for the same creek at the south end of the grounds that the engineers of 100 years ago had struggled with. Now routed under the MotoGP course, the creek was not without its own history. In a special obstacle course event in 1910, cars bounced through the creek’s ditch before scooting onto the bricks for a lap around the oval.

Like many at the Speedway, Forbes is always conscious of its history.

“I have reflected on how Mr. Andrews could never have imagined the impact his drawings would have on the American automobile and motorsports,” he said. “I have placed my hands on the very spot where a laborer laid some of the most historic brick on record. They had a job to get done - never realizing they were setting 3.2 million pieces of history.”

So much is different now, and yet an enduring link remains. From its earliest days, the Indianapolis Motor Speedway has demonstrated leadership in providing the greatest course in the world in playing host to the world’s greatest competitors.