Indianapolis 500 Fun Facts

Month of Mayhem

1995 Month of May

[Originally written and published in 2015.]

Twenty years ago, the defending champions failed to qualify for Race Day. A first-lap, first-turn crash left one driver unconscious and several others rattled. In the final laps, a driver named Goodyear, on Firestone tires, had the lead one moment and agony the next – all without ever slowing down. This was the 1995 Indianapolis 500.

Story by John Schwarb | Original Design by Zach Hudson | Video by Chris Cross | IMS.com

As the 79th Indianapolis 500 crawled under caution with 10 laps to go, Jacques Villeneuve danced his car left and right down the backstretch in a tactical chess game.

Eighteen cars remained on the track, but that moment belonged to just two, the leader and the follower: Scott Goodyear, a 35-year-old native of Ontario, Canada, and Jacques Villeneuve, a 24-year-old from Quebec.

The view of the leader’s rear wing was familiar for Villeneuve. The previous year, at the 1994 Indianapolis 500, Villeneuve was a surprising runner-up. Sitting second a year later was even more of a surprise because he was in that slot after rebounding from a two-lap penalty, levied after he passed the Pace Car on Lap 36 of 200.

Goodyear, meanwhile, was right where he belonged. He led in what might have been the single best car in the field, a Reynard chassis with a Honda engine and Firestone tires that qualified on the front row and stayed among the leaders all day. Coming into the 1995 “500,” Goodyear had five starts and a runner-up story like no other: In 1992, he had driven from the 33rd and last position on the grid to within a whisper of winning, losing to Al Unser Jr. by 43 one-thousandths of a second in the race’s closest finish.

But in 1995, everything had fallen Goodyear’s way, and he sat 10 laps from racing immortality. Other title hopefuls had crashed out or otherwise lost sight of the lead in the trying 500-mile test of car, driver and team. Still lurking was the intentionally distracting Villeneuve, trying to win more on guile than speed.

Villeneuve's blue and white No. 27 Reynard/Ford Cosworth darted left and right, filling Goodyear’s mirrors. Villeneuve would lurch up to the leader’s rear wing, then fall back. The Chevrolet Corvette Pace Car – on the track following a Lap 185 accident by then-second place car Scott Pruett – continued well ahead, driven by U.S. Auto Club official Don Bailey.

“I just decided to put pressure on Scott to see if I could make him crack,” Villeneuve said.

Goodyear kept his mind on what was ahead, not the car behind him.

“I’m just making sure that everything is as it needs to be, getting ready for the restart,” he said. “Listening to the team, they’re telling you how many more laps before you go green. Looking at the track to make sure there’s nothing else that the cleanup crew has missed. You’re just getting ready for when they tell you it’s going to be green next time.”

The moment arrived. The Pace Car worked through Turn 3 and the short chute, the field still well behind. But as it took its final sweeping curve of Turn 4, it had company.

Goodyear was there, and he was on the gas.

The first week: Speed and struggle

The story of the 1995 Indianapolis 500 begins with the 1994 Indianapolis 500, which was more rout than race. Team Penske arrived at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway that year with a secretly built Mercedes Benz-branded Ilmor pushrod engine, and teammates Al Unser Jr. and Emerson Fittipaldi dominated in qualifying first and third, then combined in the race to lead all but seven laps. Unser Jr. drank the winner’s milk after Fittipaldi crashed with 15 laps to go.

A year later, as drivers and their caravans filed into the infield at 16th and Georgetown to set up for May 1995, Penske was once again expected to be the team to beat. It had the pedigree: Three of the four previous “500” titles belonged to Penske. It had the talent: The 1995 Penske drivers were Al Unser Jr., who had won in 1994 and 1992, when he was driving for Galles-Kraco Racing, and Emerson Fittipaldi, the 1989 and 1993 winner. And it had the momentum: The team was heating up in the 1995 IndyCar season. Fittipaldi had won the series race prior to the Indianapolis 500. Unser had won the race before that.

Team Penske’s first laps in practice for the 1995 Indianapolis 500 came on Day 2 of the Month of May, on Sunday, May 7. Fittipaldi and Unser each turned laps in Penske Mercedes, but the fastest cars that day were both from Team Menard: Arie Luyendyk, the 1990 winner, and Scott Brayton.

And that’s how it stayed all week. Brayton and Luyendyk took the top two spots on the speed chart every day but one, working together with their Buick V-6 engines to log the fastest laps in the history of the Speedway. They were a hair short of 235 mph. On Day 6 of practice, two days before Pole Day, a record eight drivers exceeded 230 mph. A Brazilian named Andre Ribiero was turning the fastest laps ever for a rookie; Goodyear was setting marks as the fastest Canadian ever seen at Indy.

Notably absent, however, was any show of strength from Team Penske. Through the first six days of practice, Unser sat 28th on the speed chart. Fittipaldi was 29th.

RICHARD BUCK (Chief mechanic for Unser): “USAC saw the domination of the 1994 Indy 500 and made some adjustments, which sanctioning bodies do. They made one set of adjustments, but there was another set of adjustments that came down in that motor for Indy, and that put us in a box. That was the package we had elected to go with based on the initial communications, and then more adjustments were made before we got there.”

RICK RINAMAN (Chief mechanic for Fittipaldi): “Yes, we didn’t have that engine, but we surely felt capable of doing the same thing. The big disappointment was not getting up to speed, realizing that maybe we didn’t have as good a car as we thought we did. The engine was doing all the work.”

AL UNSER JR.: “The handling of the car went away. We just couldn’t put our finger on it. We had enough power – we just couldn’t get the car going through the corner. From the middle on out, it would understeer. When we were trying to fix the understeer, then it started making the entry too quick. We just couldn’t get it working.”

JOHN CUMMISKEY (mechanic for Unser): “We didn’t get any help from USAC – that was pretty evident straight away. Had a lot of issues with the pop-off valves. I remember going to the pop-off valve office every day, multiple times. After a while, it didn’t make our lives easy. There were certainly some bad feelings from the year before.”

BUCK: “We struggled.”

The new rules were no surprise as the month began. But Penske’s inability to succeed in spite of them? That was a shock.

Pole Day: The no-shows

In 1995, drivers had two weekends available to use as many as three qualification attempts to put their cars on the grid for the Indianapolis 500. But there was only one Pole Day, one chance to get the cherished No. 1 position. Winning the pole at Indy represented both a meaningful and mythical advantage – on Race Day it meant glorious, traffic-free clean air at the front of the pack, and for two weeks leading up to the race it meant valuable hype and publicity for a team and its sponsors.

Al Unser Jr. won the pole in 1994, giving Team Penske its sixth pole in nine years.

As had been the custom in recent years, rain delayed the proceedings on Pole Day on Saturday, May 13, and a qualifying time wasn’t posted until 4:49 p.m. by rookie Alessandro Zampedri.

Nine minutes later, Arie Luyendyk laid down a four-lap average of 231.031 mph in gusty conditions. Some 20 minutes after that, Luyendyk’s teammate Scott Brayton turned a 231.604 mph qualifying effort.

When the first run through the qualifying order ended the next day, the fastest front row in race history became official. Brayton was on the pole with Luyendyk alongside him, and Scott Goodyear took the third spot with his 230.759 mph average. Behind those three, 22 more drivers had successfully qualified for the race, with the slowest effort from Eliseo Salazar, with a 225.023 mph average.

Team Penske’s two cars were not among those qualifiers. Neither had even made an attempt. Roger Penske first arrived at the Indianapolis 500 as an owner in 1969 and, save some rainout years, 1995 was the first time his team – among the richest in resources and talent in motorsports – had not had a first-weekend qualifier.

ROGER PENSKE (to the Indianapolis Star in 1995): “It’s nothing to do with power and speed. It’s strictly trying to be able to put your foot down and drive through the corners. We haven’t given them a chassis that they can maximize the car in.”

CUMMISKEY: “At that point we were scrambling so much just to figure something out. The managers and their engineers had their hands full. We all had our hands full.”

UNSER: “We really weren’t panicking at that time. We honestly thought we could get the car working during that second week of practice.”

BUCK: One of the beauties of building your cars and having your own engine package was when you got it right, it was awesome. But when you had some things wrong, you were the only ones to sort it out. That first weekend was a blur.”

The tire war: ‘Get back to Indianapolis’

Firestone had left IndyCar racing and the Indianapolis 500 after 1974, turning the series into a one-tire sport. For 20 years, every team raced on Goodyears, and the tire owned a 23-year “500” winning streak coming into 1995.

But that year also marked the return of Firestone. A number of teams used them in 1995, including Patrick Racing, which fielded just one car driven by veteran Scott Pruett. He had spent the previous year helping Firestone get ready for its comeback at Indy, logging nearly 14,000 miles of testing.

The team’s work was already paying off: Coming into May, Pruett led the season standings. And as May wore on, Firestone’s reputation grew.

Team Menard’s top two qualifiers carried Goodyear tires, while third-qualifying Scott Goodyear and four more of the top 12 cars on the grid had Firestones. After a two-decade hiatus, the tire war was back at Indy.

DALE HARRIGLE (Bridgestone Americas manager of race tire development): “In 1988, Bridgestone Corporation bought the Firestone Tire and Rubber Company. One of the things Bridgestone did after they had bought Firestone was go to the dealers and ask, ‘What could we do to reenergize the Firestone brand?’ A lot of our tire dealers said, ‘Get back to Indianapolis.’”

SCOTT PRUETT: “Thirteen thousand eight hundred test miles was the number, and you know what? I dug it. You make out of it what you want. I always kept my eye on the prize. I knew the harder I worked, the more deliberate I was, the harder I drove, the more consistent car I drove, the better product I could develop to go racing with. Over all those miles, my focus was, I’m doing all these miles in 1994 to go racing in 1995.”

ROBIN MILLER (associate sports editor of the Indianapolis Star): “I remember calling Pruett in the middle of July or August in ’94. ‘Hey, is the tire a piece of (expletive)?’ He said, ‘A piece of (expletive)? Yeah, write that, then nobody’s going to want it.’”

HARRIGLE: “A lot of the chatter around Indianapolis was that the Firestone tires were only good for a couple laps, that we didn’t bring a race tire, we brought more of a qualifying tire. We knew we brought a race tire.”

PRUETT: “We were confident of what was coming. Then when we got there, it was ‘Wow, this is going to be good.’ We knew we had a better tire. I could go anywhere I wanted.”

SCOTT SHARP: “The package was really good at that point in time for the Firestones, especially the Firestone Reynard cars. The Lola/Goodyear package wasn’t the package to be on.”

DERRICK WALKER (Owner, Walker Racing, ran Goodyears): “Ours would only have a few laps in them, and then they’d start to degrade. The rumors – stuff filtered out about what pressures they were running, how consistent their stagger was.”

PRUETT: “Cheater tires, illegal chemicals, they were only available in Japan, they aren’t legal over here, they were doing illegal stuff in Japan to build these tires for the Speedway. Every sort of negative spin on the fact that Bridgestone/Firestone was doing a great job.”

HARRIGLE: “It was quite fun. They referred to the soft tires as ‘gumballs,’ and we had actually talked about getting one of those gumball machines from a grocery store and putting it in the garage.”

JIMMY VASSER: “As the month went on, you could see that Firestone was getting stronger.”

CHEEVER: “It was nothing that we could do to change as a team. It was a non-discussion. We had what we had. I didn’t have the option of getting it. Unless there was a way to get (owner A.J.) Foyt to change tires, and I don’t even think God could do that.”

HARRIGLE: “There were plenty of people in the garage that were convinced that we were going to have to pit on Lap 10, we were going to have to pit on Lap 15. But from the testing we did, we knew what the tires would be capable of. We were confident that we would be fine.”

The second week: Calling in favors

Photo: Al Unser Jr. and Roger Penske, the winning driver and owner of 1994, failed to make the field a year later.

After its dominating effort on Pole Day, Team Menard’s garages were closed on Monday, May 15, as the run up to the second qualifying weekend began. A large sign on one door read “GONE FISHIN’.”

Less enjoyable fishing was going on in the Penske garages. After failing to qualify either of its drivers on the first weekend, Penske moved away from its ’95 Mercedes. Unser’s 1994 winner was back on the track after being parked in the basement of Roger Penske’s Toyota dealership in Downey, California. Fittipaldi drove it in what a team spokesman said was “to baseline a setup for comparison” to the ’95 cars. In a busy day of 59 laps turned, Fittipaldi’s top speed was 220.745 mph.

On Tuesday, a Reynard chassis was borrowed from Roberto Guerrero’s team, and Unser drove it for 44 laps. His top speed was 218.050 mph.

Wednesday was a washout at the Speedway, but there was big news from Penske’s garage: 1986 Indy 500 champion Bobby Rahal and his Rahal-Hogan Racing team would loan their backup Lolas, a twist from the previous year, when Rahal had borrowed a Penske car to make the 1994 field.

The next day, Fittipaldi began working with the Lola. On Friday, he turned a lap at 227.814 mph, faster than many of the cars that had qualified the previous weekend. Penske announced that it would no longer be using the Reynards.

BOBBY RAHAL: “The tables turned. We gave him two of our cars – our backup cars, which was kind of risky. If we needed them, he had them. But Roger had helped us out when we needed it the year before, so we returned the favor.”

CUMMISKEY: “We were thrashing like crazy. That Reynard was a piece of junk. I remember trying to get that thing to where it was just safe enough to drive around the racetrack.”

RINAMAN: “Myself and Richard Buck went with Roger over to Rahal’s motor home, trying to hash out what we could do. Rahal wanted to help us. I can remember sitting in that motor home – ‘This is what we can do, the weather is going to play a factor, do we jump in a new car that we haven’t worked with and try to get it up to speed?’ That was the intense part of it. Once the decision was made, then it was smooth sailing, everybody knew the job that they had to do, and we got to it.”

UNSER: “The Lola was a pretty good car. We got it dialed in pretty good.”

Bump Day

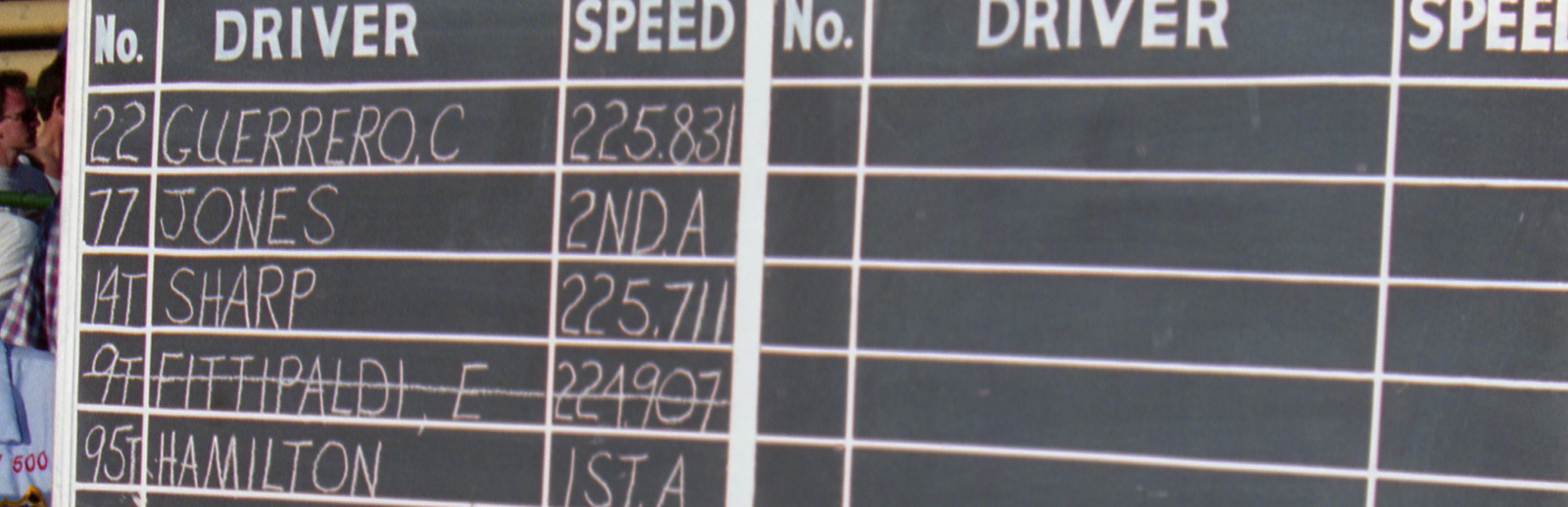

Photo: A chalkboard on the Pit Lane showed Fittipaldi’s fate at the end of Bump Day.

Five more cars filled positions on the starting grid on the third day of qualifying for 1995. But still, none belonged to Team Penske.

During qualifying attempts, teams can “wave off” their try if the speeds are undesirable, reserving that turn if they still have attempts remaining and time allows at the end of the qualifying session. Team Penske waved off Unser’s first attempt Saturday, May 20, after two laps in the low 224s. On Unser’s second attempt, he and the Lola improved from 223.959 in the first lap to 225.434 mph in the second, only to have the engine let go on the third lap and force the team into another wave-off.

Fittipaldi showed more speed in his third-day attempt with what would have been a mid-225 average but was waved off on the final lap by Roger Penske, who felt the same speed would be achievable on Bump Day, when a race position could be ensured. Thousands of fans turned out to see if he was right.

“Bump Day,” as Sunday’s final day of qualifying was then known, represented the last chance to earn a spot in the race. Once all 33 spots in the field were filled, other teams could “bump” their way in ahead of slower cars. Bump Day meant desperation, gamesmanship and keeping an eye on the clock.

At 6 p.m., a gun would be fired. At that point, the field would be locked for the 1995 Indianapolis 500.

The day opened at noon Sunday, May 21, when Carlos Guerrero became the 31st qualifier. Davy Jones made an attempt, but waved it off.

Then, for the next five hours, no one rolled into the qualifying line. Teams might be desperate for a spot – but not desperate enough to run their laps during the day’s top temperatures, when engines had to work harder and cars recorded slower times.

By 5 p.m., the sun was fading, the track cooling. At 5:07 p.m., Scott Sharp qualified his car for owner A.J. Foyt. Next came Fittipaldi, whose run of 224.907 in a Lola put him – and, for the first time all month, Team Penske – on the grid.

The first “bump” came at 5:19 p.m. when Jones jumped into the 32nd spot on the grid at 225.135. Fittipaldi moved to the 33rd “bubble” position.

Stefan Johansson was next out, but after two subpar attempts, his team waved him off. Another driver, Marco Greco, tried but was also waved off by his team.

Unser’s try at 5:31 p.m. was doomed with a 221.992 mph first lap after his pop-off valve – that same piece of equipment that had led his team to multiple visits to the U.S. Auto Club office that month – blew atop the engine, releasing air from the engine and killing its power. His third and final attempt wasn’t enough to make the field.

Jeff Ward, Greco and Davey Hamilton tried again, and all were waved off. Fittipaldi inched closer to making the race.

At 5:48 p.m., Johansson still had one attempt remaining. He had driven a ’94 Penske Mercedes in the opening week at Indianapolis, but his team, Bettenhausen Motorsports, abandoned the same car that Team Penske did, in their case in favor of a ’94 Reynard/Ford Cosworth that had been driven in the 1994 Indianapolis 500 by Mauricio Gugelmin.

Johansson’s first lap was 224.826 mph.

His second was 225.739.

His third was 225.921.

His fourth and final lap was 225.705, for a four-lap average of 225.547. Johansson landed 31st on the grid, bumping Emerson Fittipaldi out of the top 33. The difference between the two cars’ qualifying efforts was less than half a second over the 10 miles.

The gun for the session sounded at 6 p.m.

Stefan Johansson Bump Day Qualifying

Throughout the month, the idea that Roger Penske would not have a team in the Indianapolis 500 had seemed a remote possibility. Surely, onlookers assumed, they would maneuver their way onto the field.

But in that moment, two two-time winners of the “500” were shut out of the race. For the first time since 1962, a member of the Unser family was not in the starting field. “Little Al” became the first defending champion to fail to qualify the following year.

UNSER: “I was just dumbfounded. Just devastated and heartbroken. To miss the show at Indy was beyond my wildest dreams. I never even imagined that was a possibility, especially with Roger Penske.”

BUCK: “That final hour probably aged all of us 10 years.”

CHRISTIAN FITTIPALDI (Emerson Fittipaldi’s nephew): “It was hard for the Fittipaldi family. I wanted to race with Emerson. As far as him not making the field, that never crossed my mind.”

RINAMAN: “Emerson took it pretty hard. He had a lot to prove after what happened in ’94. Not making the field was as devastating, if not more, than the ’94 crash.”

STEFAN JOHANSSON: “There was no way I was not going to get in. I told my engineer to take out all the downforce. ‘Just make it as low as you can.’ Normally you go in quarter-degree increments – it was a couple of degrees. I remember them telling me, ‘Listen, you don’t have to do this.’ I went down into Turn 1 on the warmup lap, I put my left foot on top of the right foot, not to lift. If you lift, it’s all over. I had no idea what the car was going to do. Thankfully, it stuck.”

MILLER: “There were 30 or 40 thousand people there the last day of qualifying. Half of them cheering for Penske, half of them were cheering against them. It was amazing. But everybody loved Al Unser Jr. They didn’t want him to miss it.”

PAUL PAGE (ABC broadcaster): “I talked ABC into putting Derek (Daly) and I pit-side right there at the final position before they went out to qualify. It was something we’d never done before. It was really cool television – us sitting there, we had the full sense of it. I remember looking up and down the line and being pretty impressed – you’ve got every luminary in the sport standing in the pits for these last runs.”

VASSER: “You couldn’t miss it. That’s drama like no other.”

SCOTT GOODYEAR: “It’s interesting to see what goes on – especially interesting when it’s Team Penske looking to get into the field on the last day. That never happens. Indianapolis doesn’t choose any favorites.”

LYN ST. JAMES: “All of us are thinking, this is unbelievable and unheard of. But of course, deep down, of course they’re going to figure it out.”

RAHAL: “I suppose people were a bit shocked when I didn’t qualify, but for Roger not to qualify? That’s a different league.”

ST. JAMES: We’re still on pit lane, the gun goes off, Penske isn’t in it. I get out of the car, and my sponsor is like a frickin’ peacock walking up and down the pit lane. I went over and said something like, ‘We’re in.’ And he goes, ‘This is a moment in my life when I have outdone Roger Penske.’ I’m like, ‘You got lucky. It had nothing to do with you.’”

EDDIE CHEEVER: “I’m embarrassed to admit that I did find a little bit of humor in it. The racing gods had paid them back for what happened the year before.”

CUMMISKEY: “The biggest thing I remember is pushing the car through the Gasoline Alley opening and watching the USAC people high-fiving each other. I wanted to punch them in the face.”

RINAMAN: “I took that as maybe a compliment that we’re not racing, but that was probably the most disappointing thing. We were like the New York Yankees, and they hated to see people win all the time.”

PENSKE (to the Indianapolis Star on Sunday evening): “We didn’t execute very well, and it’s a shame these two drivers didn’t make the race because it’s my responsibility to provide the package for them.”

BUCK: “You’re expected to win. That’s how we all felt walking into every racetrack. To go from that to missing the Indy 500 was a heavy weight. You let yourself down, you let Philip Morris down – they were personal friends, everyone came to the track from there. All the Penske companies, the people that worked at the truck rental place, Detroit Diesel, every business – we were their football team. We were their heroes, and we let them down that day.”

Starting Grid for the 1995 Indianapolis 500

| 1 | Scott Brayton | Lola / Menard |

| 2 | Arie Luyendyk | Lola / Menard |

| 3 | Scott Goodyear | Reynard / Honda |

| 4 | Michael Andretti | Lola / Ford Cosworth |

| 5 | Jacques Villeneuve | Reynard / Ford Cosworth |

| 6 | Mauricio Gugulmin | Reynard / Ford Cosworth |

| 7 | Robby Gordon | Reynard / Ford Cosworth |

| 8 | Scott Pruett | Lola / Ford Cosworth |

| 9 | Jimmy Vasser | Reynard / Ford Cosworth |

| 10 | Hiro Matsushita | Reynard / Ford Cosworth |

| 11 | Stan Fox | Reynard / Ford Cosworth |

| 12 | Andre Ribiero | Reynard / Honda |

| 13 | Roberto Guerrero | Reynard / Mercedes Benz |

| 14 | Eddie Cheever Jr. | Lola / Ford Cosworth |

| 15 | Teo Fabi | Reynard / Ford Cosworth |

| 16 | Paul Tracy | Lola / Ford Cosworth |

| 17 | Alessandro Zampedri | Lola / Ford Cosworth |

| 18 | Danny Sullivan | Reynard / Ford Cosworth |

| 19 | Gil de Ferran | Reynard / Mercedes Benz |

| 20 | Hideshi Matsuda | Lola / Ford Cosworth |

| 21 | Bobby Rahal | Lola / Mercedes Benz |

| 22 | Raul Boesel | Lola / Mercedes Benz |

| 23 | Buddy Lazier | Lola / Menard |

| 24 | Eliseo Salazar | Lola / Ford Cosworth |

| 25 | Adrian Fernandez | Lola / Mercedes Benz |

| 26 | Eric Bachelart | Lola / Ford Cosworth |

| 27 | Christian Fittipaldi | Reynard / Ford Cosworth |

| 28 | Lyn St. James | Lola / Ford Cosworth |

| 29 | Carlos Guerrero | Lola / Ford Cosworth |

| 30 | Scott Sharp | Lola / Ford Cosworth |

| 31 | Stefan Johansson | Reynard / Ford Cosworth |

| 32 | Davy Jones | Lola / Ford Cosworth |

| 33 | Bryan Herta* | Reynard / Ford Cosworth |

*Herta started at the rear of the field after moving to a backup car following a practice crash in his primary car

Failed to qualify: Jim Crawford, Emerson Fittipaldi, Franck Freon, Marco Greco, Michael Greenfield, Mike Groff, Dean Hall, Davey Hamilton, Johnny Parsons Jr., Tero Palmroth, Al Unser Jr., Jeff Ward.

The 1995 Indianapolis 500, Lap 1: "A Flash of Purple"

Photo: Despite this violent crash through the south short chute, Stan Fox incredibly had no lower-body injuries.

At 5 a.m. Sunday, May 28, the traditional military bomb signaled the opening of the Speedway gates, and a steady stream of humanity began to fill the 2.5-mile oval. At 9:45 a.m., the starting grid filled as the Purdue University band played “On the Banks of the Wabash.”

At just before a quarter to 11, Florence Henderson delivered her stirring national anthem. Next came the invocation, “Taps,” the flyover and another job for the Purdue band – “Back Home Again in Indiana” with Jim Nabors.

At 10:54 a.m., Mary Fendrich Hulman commanded one lady and 32 gentlemen to start their engines. One minute later, the field of 33 cars pulled away behind the 1995 Chevrolet Corvette Pace Car, driven by General Motors Corp. vice president Jim Perkins – the ceremonial driver who started the “500” before a U.S. Auto Club official took over the duties during cautions. Robby Gordon pitted on the second parade lap with throttle and radio problems but rejoined the field as the green flag for the 79th Indianapolis 500 flew at 11:01 a.m.

As the field headed for Turn 1, and 11th-place qualifier Stan Fox moved too low to the inside, spun up the track and into the outside wall, collecting Eddie Cheever in the process while Lyn St. James and Carlos Guerrero collided in the aftermath. Fox’s Reynard chassis shattered into a cloud of debris, and the driver’s tub split in half, leaving his legs exposed.

The yellow was out, seconds after the green.

CHEEVER: “A car ahead of me changed position, and I went up. I never really liked being up high in the first corner, but I went up high because I didn’t have a choice. Everything looked OK. Then, out of my left side, I see a shadow coming. And then Stan ran into the side of me like a torpedo.”

VASSER: “It happened right behind me. I saw it in my mirror. I saw a flash of purple. The car was weird purple. He almost collected me in the rear.”

ST. JAMES: “I almost cleared Carlos, at which time I would have cleared the accident. But I clipped him.”

RAHAL: “I dove for the inside. When stuff like that happens all you see is stuff flying. You don’t really see. I was looking left, trying to figure out how I was going to keep from getting involved.”

C. FITTIPALDI: “I could see that accident was pretty intense because I managed to see Stan’s car flying, and I was four rows behind.”

MARTIN SEPPALA (Associated Press photographer): “I remember seeing the nose of Stan’s car almost in the grass. It might have been in the grass. And I thought, ‘OK, this is not good.’ Then the back end came around. The minute the back end breaks loose, you see the tire smoke. I just pushed the button and followed through. I let up when I saw him get to the short chute, and then he just kept going and ended up clear down in Turn 2.”

CHEEVER: “I stop, and my instinct is I’m p----- off – I cannot believe that somebody would hit me. We’re not even fourth gear in the middle of (expletive) Turn 1. I go up and look inside, and Stan’s messed up. He’s got blood coming out of his nose, his eyes are rolled back in his head. Somebody took his helmet off, and I pulled out his earplugs. Don’t ask me why – I thought it would help him. And then I just walked away.”

DAVEY HAMILTON (Fox’s teammate with Hemelgarn Racing, failed to qualify): “I was going to spot for him in Turn 4. I don’t need to tell you that I didn’t get anything done.”

BRYAN HERTA: “I was young. I’d never seen an accident like that before. As a driver you try to compartmentalize and block stuff out, but I remember asking about him on the radio. The team just told me, ‘Focus on your race.’”

JACQUES VILLENEUVE: “They wouldn’t tell you on the radio. They wouldn’t want you to worry about that. If every time someone crashes you think something bad happened, you wouldn’t be able to drive.”

GOODYEAR: “You go by and you occupy yourself doing something in the car. Checking your dash, whatever. You’re not going to look to see what’s going on.”

PAGE: “I thought we’d lost Stan for half the race until they finally gave us some feedback – serious head injury.”

Passing the Pace Car, part I

The race went green again on Lap 9 following the cleanup. Scott Goodyear, having quickly passed Brayton and Luyendyk on the outside at the start, led all the laps under caution, becoming the first driver to lead at Indy on Firestone tires since Al Unser in 1973.

Luyendyk lurked in second through the caution period and moved to the front on Lap 10. Michael Andretti then took the point on Lap 17, a familiar sight at the “500.”

No driver in the field had led more career laps at the Speedway, though Andretti infamously had no wins to show for it. In 1992, he had led 160 laps but coasted to a stop 11 laps from the end with a fuel pump failure. In 1991, he had led with 12 laps remaining but couldn’t win a back-and-forth battle with Rick Mears.

Andretti pitted on Lap 32, and Goodyear took the lead again for three laps. On Lap 36, Jacques Villeneuve took an unexpected stint in the lead that turned disastrous when a caution for debris came out one lap later.

BARRY GREEN (Villeneuve’s car owner): “We wanted not to be anywhere close to the front in the first 450 miles. The plan was to run fifth through 10th, just cruise and be happy. We were around sixth, seventh.”

VILLENEUVE: “We were starting to run out of fuel, trying to figure out whether we could get an extra lap or not. We took the lead because others were pitting. Then the yellow comes out.”

GREEN: “All of a sudden, we are in the lead, and I’m not even paying attention because we’re not supposed to be in the lead. We don’t want to be in the lead and weren’t in the lead a lap ago. We were miles from the lead.”

VILLENEUVE: “When I got to the Pace Car, they didn’t wave me to stop, so I just drove by. The second time by, I couldn’t believe they hadn’t picked up the leader. I didn’t know it was me.”

GREEN: “I believe it is our responsibility, the driver’s responsibility, to find the Pace Car and pack up, but he gets waved through not once but twice. The officials came on the radio and told us we had a two-lap penalty for passing the Pace Car, which waved us by twice.”

TOM BINFORD (USAC chief steward, after the race): “It was a flagrant pass. I think there were three instances. He just didn’t slow down. He just acted as if there hadn’t been a yellow flag at all. I think it was pretty obvious that he knew he was the leader.”

VILLENEUVE: “It was a downer, but I had a very positive crew. We didn’t think we could win, but we could get good points for the championship.”

Andretti regained the lead after Villeneuve’s penalty was assessed on Lap 39 and held it for 28 laps until Lap 66 and a scheduled pit stop. But Andretti would come to the pits for good 11 laps later after hitting the wall coming out of Turn 4 while trying to avoid leader Mauricio Gugelmin, who was working his way to pit road.

MICHAEL ANDRETTI (On the ABC broadcast): “I guess Mauricio was coming into the pits. He slowed down, and I had a run and went to the outside because I didn’t want to hit him. It’s like ice. I hit the wall. Beautiful (car), best I ever had here.”

The latter stages

Gugelmin, the popular Brazilian, had three stints in the lead for 59 laps in his Reynard/Ford Cosworth through the middle stages of the race, but with 50 laps to go the top four were Jimmy Vasser, Jacques Villeneuve, Scott Goodyear and Scott Pruett.

Two were on Goodyear tires, two were on Firestones. Three drove Reynards, one had a Lola (Pruett). And three drove Ford Cosworth engines, while one had a Honda (Goodyear).

On Lap 156, the unthinkable happened: Villeneuve, who had clawed his way back from the two-lap penalty for passing the Pace Car under yellow in Lap 39, took the lead from Vasser.

VILLENEUVE: “Every lap was a qualie lap, being aggressive, pushing. We didn’t have a choice. It made it fun and exciting, but that’s not normally how you want to attack the Indy 500.”

GREEN: “We figured out what we had to do and when we had to go hard. We ran out of fuel coming into the pit lane twice. One time we had to use the starter motor. We also completely wore out the right rear (tire) twice, through to the cambers. That’s how hard he was driving. We did it on one or two less stops than we were going to.”

VILLENEUVE: “I was just happy that I was on the lead lap. I thought we’d get some good points from this race. Every lap I was looking at the (scoring) post. Early on I could see I was at the bottom. Then I saw I was climbing up.”

On Lap 163, Pruett took the lead for the first time when a yellow came out for a crash involving Jones. Vasser got the lead back four laps later, then saw his hopes end on Lap 170 while battling Pruett.

Pruett, on his Firestones, made a pass at the end of the back straight to retake the top spot, and Vasser, moving too high on the track to an area where his tires couldn’t find grip, crashed into the outside wall in Turn 3. Upon exiting his car in the north short chute, Vasser waited for Pruett to pass by under caution with his arms in the air, gesturing.

BOBBY UNSER (on the ABC broadcast): “I think he’s wrong. I think he’s looking for an excuse, anxious at the end of the day.”

VASSER: “It wasn’t one of my prouder moments. I thought at the time maybe he stuck me in the marbles, but in reality it was a racing thing – 30 to go at Indy, he had a little run on me, got a little inside, I tried to stay on the inside. Just touched the edge of the marbles, and once you get to the marbles you can’t even steer.

“I was upset, but when I got back (owner) Chip (Ganassi) said – and it was my first year with Chip – ‘Hey, you crash out racing for the lead, we don’t have a problem. Don’t be crashing out when you’re running for 15th.”

RAHAL: “There were a lot of marbles on the track. It was the most mentally exhausting ‘500’ I’d run because you didn’t dare get off-line. If you got off-line a little bit, you’re in the wall.”

PRUETT: “I could go anywhere – high, low, inside, outside. I could do anything I wanted. I could just cut my way through traffic. It was a great day at the races.”

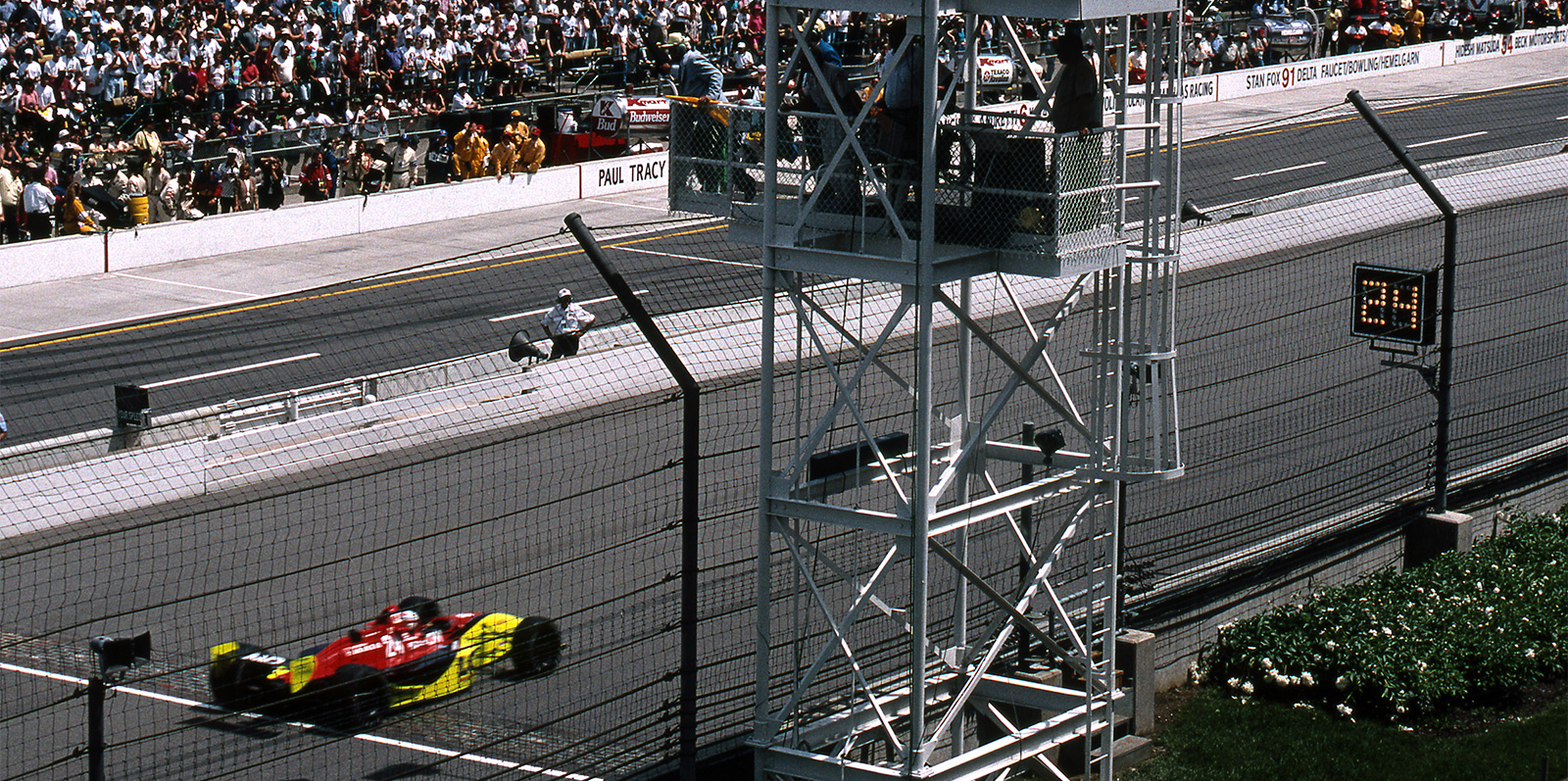

Pruett led again under caution but surrendered the lead on the Lap 176 restart, this time to Goodyear, who came flying off Turn 4. Pruett settled into second until his great day ended on Lap 185 after running through oil from Raul Boesel, who had blown an oil line but continued limping under green.

Pruett tagged the outside wall of Turn 2, skidded across the backstretch and smashed into the inside fence, shearing off the rear wheels and rear suspension of his Lola.

PRUETT: “I slowed up on that restart, I came around Turn 3 into Turn 4, saw the Pace Car and said, ‘Uh, I can’t pass him.’ Goodyear got a big run and passed me. I’m thinking as soon as he hits traffic, I’m going to work my way by.

“Raul told me later he blew up. Dumped oil all over the track – but the yellows didn’t come until I crashed. Just one of those unfortunate things.”

HARRIGLE: “The Goodyear execs were so upset with 20 laps to go that they had actually left IMS. When Pruett crashed, they quickly got in the car and came back.”

The yellow was out, and Scott Goodyear led.

The finish

Photo: Scott Goodyear was shown the black flag on Lap 192. He ignored the directive to serve a stop-and-go penalty.

Goodyear sat on the lead for six laps of caution in the closing moments of the world’s largest single-day sporting event. The day could not have gone much better for him up to that point.

The only cars stronger than his in qualifying, Team Menard’s Brayton and Luyendyk, were a shadow of their practice and Pole Day selves in the race and off the lead lap. Pruett, a fellow Firestone driver, had crashed out of the fight, as had Vasser.

There were a few other notable performers: Past champion Rahal was having a good run, as were rookies Fittipaldi and Eliseo Salazar.

But as far as real threats, only Jacques Villeneuve remained, dancing behind Goodyear under yellow in an attempt to distract the leader.

The gamesmanship lasted all the way down the backstretch of Lap 191 as the Pace Car ahead continued on the inside of the track, heading to pit road and the end of that caution flag.

Goodyear punched the gas and took off midway through Turn 4 of Lap 191.

And passed the Chevrolet Corvette along the way.

BOBBY UNSER (on the ABC broadcast): “Whoa! He blew the Pace Car right off!”

VILLENEUVE: “I wasn’t thinking that he would be going too early. I just wanted to put pressure on him, just showing him I was there, I’m not going to make it easy. I wasn’t expecting that.”

PRUETT: “I was back in medical from my crash. I’m looking on the monitors. It’s still under yellow, it’s coming to green, I’m watching the Pace Car, and I see Goodyear pass the Pace Car. All those things I didn’t do and was careful of – he did all those things.”

WALKER: I saw him pass the Pace Car and said, ‘Ooh, that’s a problem. He’s not going to get away with that.’”

PAGE: It was one of the hip-pocket rules. We all thought we understood it; it turns out we didn’t. CART (sanctioning body of the PPG Indy Car World Series) ran it differently – once the Pace Car pulled off the course, pulled down, the leader took control of the race and took you to the green. The logic was the leader had a better sense of what the pace ought to be coming to the green, to help everybody else. So when that started to happen, we weren’t sure. None of us had a clear understanding of that rule operating at the Indy 500. My producer, Bob Goodrich, 30 seconds later starts yelling at me. ‘He’s passed the Pace Car, he’s passed the Pace Car!’”

GOODYEAR: “He’s supposed to accelerate away and be gone. Hopefully you don’t see him. I lagged back in Turn 3, even had it in neutral so the motor wouldn’t chug in first gear, and let him get up and away so I couldn’t see him any longer, and then once he was gone, back into first gear, got ready. And when I hammered the gas up through 3 and going through the short chute and getting into 4, he was so slow on the left-hand side that I thought he had a problem. It’s interesting that he’s off to the side, not going all that fast, thought that he would be long gone.

“As the leader of the race, my whole concern is that, boy, if I took my foot off the gas, I’m going to stack up everybody behind me, and there’s going to be a huge crash. So I keep my foot on the gas, get around the Pace Car and then just keep on going down the straightaway.”

DANNY SULLIVAN: “If you time it wrong and you come flying out of 3 and 4 and you come out of 4 and that Pace Car, you’re about to pass him, you have to check up or pay the price. And if you really check up, you can cause an accident or, more than likely, everybody else is going to pass you.”

PRUETT: “They told us in the driver’s meeting that you couldn’t pass the Pace Car. When you came to Indy, it was different than everywhere else. It was USAC.”

VASSER: “If you’re leading and you’re going to accelerate, the Pace Car’s gotta be down on pit lane before you come blowing by. That’s just dangerous. You let the Pace Car go on the back straight, then you have the field. You have the field, but you’re not supposed to pass the Pace Car. That was always the rule. The Pace Car’s usually coming down pit lane when the cars start accelerating in the short chute coming into 4. We used to get up to speed from there.”

VILLENEUVE: “He overtook the Pace Car halfway through the corner. It’s clear in the rules.”

The verdict from USAC, the referees of the Indianapolis 500, came on Lap 192.

PAGE (on the ABC broadcast): “Oh, no. The officials are now reporting they’re going to show the black flag to Scott Goodyear, the 24 car. They’re going to show the black flag to the leader of the race. Stop-and-go penalty because he passed the Pace Car before going green.”

BINFORD (after the race): “The obvious interference with the Pace Car is that he passed the Pace Car. The violation took place, and I applied the penalty. I’ve never seen a race where a car has passed the Pace Car right on the track. The observers who could see it, saw it. The Pace Car saw it. I saw it.”

GOODYEAR: “I was in disbelief. I was in disbelief because, No. 1, the Pace Car was going slow. Wasn’t out of the way, and I certainly thought that he had enough time to be gone and back around Turn 4 and pulling into the pit lane.”

RAHAL: “It was a shame. Scott and that car were the class of the field, one of the top cars all through the race. Then, at the end, he was in his own league. He was much faster than anybody else.”

MILLER: “It’s not that Scott Goodyear did some heinous thing, but you felt bad for the guy because he didn’t have to do it. Jacques Villeneuve was on Goodyears. He wasn’t going to pass Scott Goodyear on a restart. Wasn’t going to happen.”

C. FITTIPALDI: “If it was a little bit later, maybe he could have gotten away with it. When it comes down to crunch time, it’s hard. At Indy, if you lift even a little bit, it’s like throwing a parachute behind the car. Once he decided in his mind that he had to go, he had to go.”

VILLENEUVE: “In his position, I’m not sure I would have hit the brakes.”

Photo: Scott Goodyear faced a crush of media in Gasoline Alley after the race and stood by his position that he did nothing wrong.

Goodyear did not hit the brakes. He did not even slow down. He refused to come in and serve the stop-and-go, a penalty that is just as it sounds, requiring a driver to come to his pit, make a complete stop and then continue, resulting in a considerable loss of time and position. Instead, Goodyear remained on the track, on the gas – and well ahead of Villeneuve and his pursuers.

On Lap 195, USAC stopped scoring Goodyear.

BOBBY UNSER (on the ABC broadcast): “He’s probably having a hard time believing it. If I were him, I would, too. It’s such a sad thing. According to them, he did break the rules. It’s just sad to see something like that. A Pace Car should never be figured into a race win.”

GOODYEAR: “Steve Horne comes on and says, ‘They want you to come in for a drive-through.’ He was very calm on the radio. I pushed the button on the radio and said, ‘Steve, I’m not coming in. Makes no sense.’ He said, ‘OK. Keep your foot on the gas.’

“Of course I’m going to stay out. It takes me back to my karting days. They give you a black flag, and you’re not guilty of the infraction – but you come in, and they come back and say, ‘Our mistake. We’re sorry.’ You’ve now gone from leading the race or being in the top three or whatever and now back to 12th or 15th or 20th. They’re not going to put you back where you were and give you a podium finish or a victory.”

RAHAL: “You don’t want to, but they pretty much tell you what’s going to happen. You’re going to have to take your medicine, one way or another.”

WALKER: “It was weird to watch that. It didn’t look right, to be finishing the 500 with a rogue car that says.”

GOODYEAR: “It’s still disheartening when you come down off of 4, and you’re wondering whether or not they’re going to throw the checkered flag or not. And they didn’t, but you still go underneath the flag stand in first place. Just complete disappointment and just emotional thinking about it: ‘I can’t believe this.’”

The winner

Photo: Jacques Villeneuve won the Indianapolis 500 after surviving his own two-lap penalty early in the race for passing the pace car.

For the first time, a Canadian won the Indianapolis 500. Jacques Villeneuve took the lead on Lap 195 when Goodyear’s lap scoring was halted. No one else challenged Villeneuve in the final five laps. Christian Fittipaldi, a surprising young rookie runner-up, just as Villeneuve had been the previous year, finished second 2.481 seconds back.

Villeneuve’s win was improbable in every way. He drove on Goodyear tires, which had proven themselves to be the inferior product in the two-tire war, while two fast foes in the closing laps were on Firestones.

And most incredibly, Villeneuve had driven 505 miles. Five extra miles, two circuits around the massive Speedway oval, to regain the two laps taken away in the early stages.

MILLER: “The yellows fell well, and Barry Green called a really smart race. I just remember how Villeneuve looked half-shocked in Victory Lane. He was like, ‘Are you kidding me? We won?’ He wasn’t even a speck on the radar. ‘Who? Where’d he come from?’”

RAHAL: “In the end, Villeneuve won on Goodyear, but Scott Goodyear had the race won, and that was Firestone’s shot. For the Goodyear guys, that whistle they heard going past their head was that Firestone bullet that just missed.”

HARRIGLE: “Ultimately our result was better than any of us could have hoped for and what we had targeted, but we were quite disappointed.”

GOODYEAR: “Afterward, I’m very disappointed that we didn’t win the event or get credit for winning the event. Disappointed for the team, the ownership, the sponsors, Firestone, Honda. And my family – my wife was in tears. At that point in time, because I’ve been through so much racing and the highs and lows that go with it, I’m in disbelief. Is there recourse for it? I found very quickly thereafter that the chief steward’s decision is unprotestable.”

After drinking the winner’s milk, Villeneuve told the media he didn’t think he could have beaten Goodyear without the penalty. The cat-and-mouse game under yellow was his key to victory.

VILLENEUVE: “He had it in his hands. His mistake gave me the win. I was happy I pushed him into that mistake. To win, it takes more than just being fast. That was one of those moments.”

GOODYEAR: “I would say adamantly no. Wasn’t even paying that much attention to him. Your job as the first car on the start is to make sure you’re going to go as fast as you can, and that you time it right and that you get down, especially here, into Turn 1 and they don’t get a draft. Who’s to know if he would have had enough to be able to make the draft, if the timing was right on his end or what have you? Sitting in the cockpit getting ready for a restart, I’m not paying that much attention to what he’s doing back there.

“If he believes that and wants to think that, that’s all for him, but absolutely not.”

***

The winners and losers left the Speedway on Sunday night, then gathered the next night at the Indiana Convention Center for the traditional victory celebration. There, every driver is presented with a check and gets a few moments on the microphone to offer a quip, thank sponsors and, usually, congratulate the winner.

Villeneuve accepted $1,312,019 as the Indianapolis 500 champion. Goodyear received $246,403 for 14th place, where he had landed after being scored for only 195 laps.

“We’re all getting off the stage, and Tom Binford came to me. He said first off, ‘Very professional speech, thank you’ – I’m not sure if he was worried I was going to say something – and then he said, ‘You should have come in because you would have finished sixth or seventh,’” Goodyear said. “I just looked at him, and I go, ‘That was not an option. That’s not what I’m here for.’

“And I just walked away.”

1995 Indianapolis 500 Finishing Order

| 1 | Jacques Villeneuve | Reynard / Ford Cosworth | 200 | Running |

| 2 | Christian Fittipaldi | Reynard / Ford Cosworth | 200 | Running |

| 3 | Bobby Rahal | Lola / Mercedes Benz | 200 | Running |

| 4 | Eliseo Salazar | Lola / Ford Cosworth | 200 | Running |

| 5 | Robby Gordon | Reynard / Ford Cosworth | 200 | Running |

| 6 | Mauricio Gugelmin | Reynard / Ford Cosworth | 200 | Running |

| 7 | Arie Luyendyk | Lola / Menard | 200 | Running |

| 8 | Teo Fabi | Reynard / Ford Cosworth | 199 | Running |

| 9 | Danny Sullivan | Reynard / Ford Cosworth | 199 | Running |

| 10 | Hiro Matsushita | Reynard / Ford Cosworth | 199 | Running |

| 11 | Alessandro Zampedri | Lola / Ford Cosworth | 198 | Running |

| 12 | Roberto Guerrero | Reynard / Mercedes Benz | 198 | Running |

| 13 | Bryan Herta | Reynard / Ford Cosworth | 198 | Running |

| 14 | Scott Goodyear | Reynard / Honda | 195 | Penalty |

| 15 | Hideshi Matsuda | Lola / Ford Cosworth | 194 | Running |

| 16 | Stefan Johansson | Reynard / Ford Cosworth | 192 | Running |

| 17 | Scott Brayton | Lola / Menard | 190 | Running |

| 18 | Andre Ribeiro | Reynard / Honda | 187 | Running |

| 19 | Scott Pruett | Lola / Ford Cosworth | 184 | Accident |

| 20 | Raul Boesel | Lola / Mercedes Benz | 184 | Oil Line |

| 21 | Adrian Fernandez | Lola / Mercedes Benz | 176 | Engine |

| 22 | Jimmy Vasser | Reynard / Ford Cosworth | 170 | Accident |

| 23 | Davy Jones | Lola / Ford Cosworth | 161 | Accident |

| 24 | Paul Tracy | Lola / Ford Cosworth | 136 | Electrical |

| 25 | Michael Andretti | Lola / Ford Cosworth | 77 | Accident |

| 26 | Scott Sharp | Lola / Ford Cosworth | 74 | Accident |

| 27 | Buddy Lazier | Lola / Menard | 45 | Fuel System |

| 28 | Eric Bachelart | Lola / Ford Cosworth | 6 | Mechanical |

| 29 | Gil de Ferran | Reynard / Mercedes Benz | 1 | Accident |

| 30 | Stan Fox | Reynard / Ford Cosworth | 0 | Accident |

| 31 | Eddie Cheever Jr. | Lola / Ford Cosworth | 0 | Accident |

| 32 | Lyn St. James | Lola / Ford Cosworth | 0 | Accident |

| 33 | Carlos Guerrero | Lola / Ford Cosworth | 0 | Accident |

Scott Goodyear discusses the 1995 Indianapolis 500

Epilogue

When Scott Goodyear built a new home north of Indianapolis in late 1993, he had a shelf in his office trophy case specially made for a “Baby Borg” trophy he was sure he would eventually win after coming so close in 1992. He was close in ’95 and again in ’97, when he finished second to Arie Luyendyk.

But Goodyear, now a racing commentator for ABC, never won the Indianapolis 500. And that shelf? “There’s other stuff there now,” he said.

Jacques Villeneuve rode the momentum of winning the Borg-Warner Trophy all the way to the 1995 series championship, then jumped to Formula One and won its championship in 1997. He returned to the Indianapolis 500 in 2014 after a 19-year absence and finished 14th.

Tom Binford, the USAC chief steward who penalized Goodyear on Lap 192, was 71 years old at the time and had announced his retirement prior to the 1995 race. He died in 1999.

Roger Penske didn’t return to the Indianapolis 500 until 2001. His cars then won the race three consecutive years. Altogether, Penske teams have won five Indianapolis 500s since their return.

Gil de Ferran, who finished 29th as a rookie in 1995 after sustaining damage in Stan Fox’s Lap 1 accident, went on to win the 2003 Indianapolis 500 while driving for Penske.

Emerson Fittipaldi never turned another competitive lap at Indy after failing to qualify in 1995. Two-time “500” champion Al Unser Jr. returned in 2000 and made seven more starts through 2007 but never finished higher than ninth.

Longtime Penske chief mechanic Richard Buck began working with NASCAR teams in 2001 and is now managing director of the Sprint Cup Series. John Cummiskey remained with Team Penske through 1999 before moving to other Indy car teams. Rick Rinaman still works for Team Penske.

Stefan Johansson, the driver who sent Team Penske home in 1995 with his Bump Day run, never raced in another “500.” Today he is the manager of 2008 Indianapolis 500 champion Scott Dixon.

“Not a week goes by in my life that I don’t think about that race,” Scott Pruett said about 1995, his hopes of winning derailed by the Lap 185 crash. It was his last “500,” but at age 55 he still races sports cars; he finished second three straight years on the IMS road course from 2012-14 for Chip Ganassi Racing.

Jimmy Vasser returned to Indianapolis in 2000. In 2001, he finished fourth and completed all 200 laps for the only time in eight career starts.

Christian Fittipaldi, the 1995 Indianapolis 500 Rookie of the Year in what was just his third start ever on an oval track, never made another “500” start – one of only two drivers in Indianapolis 500 history to win Rookie of the Year as a runner-up finisher and never start the race again. Bobby Rahal, third in 1995, also never raced again at Indy. Nor did fellow former champion Danny Sullivan, ninth in 1995, who retired later that year after a crash at Michigan International Speedway.

The owner of Fittipaldi’s car, Derrick Walker, remains convinced today that his other entry, fifth-finishing Robby Gordon, would have won if he hadn’t taken a late pit stop because he thought a tire was going flat. In the pits it was discovered that the tire was fine. Walker is now the president of competition and operations for the Verizon IndyCar Series.

Scott Brayton, the 1995 pole-sitter who faded to 17th in the race, won the pole again in 1996 but was killed in a practice crash six days later.

Stan Fox made a full recovery from his injuries in the opening-lap crash of 1995 but never raced again. He died in 2000 in a traffic accident in New Zealand.

Eddie Cheever Jr., the driver who was also in the outside wall with Fox in the Lap 1 crash, won the Indianapolis 500 three years later in 1998.

Firestone tires were on 1996 Indianapolis 500 champion Buddy Lazier’s car and Luyendyk’s 1997 winner. Goodyear tires were on the 1998 and 1999 winners, but the company left open-wheel racing at the end of the 1999 season. Since then, Firestone tires have been on every Indy 500 winner.

In 2000, officials at the Indianapolis 500 amended race restarts. The Pace Car would pull off in Turn 1 with one lap remaining under caution, with the leader of the race pacing the field back to the green flag.

How this story was reported:

Twenty-five interviews were conducted for this story including 13 drivers from the 1995 Indianapolis 500, car owners, mechanics and media. Information was also used from Indianapolis Star archives and the Indianapolis Motor Speedway’s “Daily Trackside Report” from the 1995 Month of May.