Indianapolis 500 Has Incubated Endless Advancements in Automotive Technology, Safety

August 03, 2020 | By Marshall Pruett

The story of the Indianapolis 500 has been told 103 times by racers who’ve etched their names into The Brickyard’s lore. It’s 1911 winner Ray Harroun, 2019 victor Simon Pagenaud and hundreds of other men and women whose achievements have made the Indy 500 a cultural phenomenon.

Complementing those pioneers and heroes, the Speedway has also produced fabled cars and fabulous technologies that fueled more than a century of furious competition, inspired young mechanics and engineers, and forever changed the auto industry.

The Speedway gained notoriety as a proving ground before World War I, and with the inaugural “500” winner, Harroun’s Marmon “Wasp,” the first notable contribution from The Brickyard to America’s budding car industry was recorded.

“That car is famous for many reasons, with one being the first widely recognized use of a rear-view mirror,” says IMS historian Donald Davidson.

Two years later, the French Peugeot team and its 1913 “500” winner would, through a remarkable set of interconnected events, unknowingly birth Indy’s most successful racing engine and advance the use of turbocharging in production cars.

With World War I raging at home, Peugeot’s factory program ended following the 1914 race. Its stable of cars were left behind, made their way into private hands, and with many drivers keen to use the pedigreed cars, finding an American solution to look after the giant 448 cubic-inch (7.3-liter) four-cylinder engines was necessary. Enter Harry Miller and 1914 Peugeot with a blown engine.

There was no hope of receiving blueprints from Peugeot’s factory in war-torn European to replicate the broken engine, so from his shop in Los Angeles, Miller, along with employees Fred Offenhauser and John Edwards, made new drawings using their favorite aspects of the French twin-cam four-cylinder powerplant while incorporating a few ideas of their own.

Move ahead to the 1920s, and the same basic Peugeot layout with an integrated twin-cam cylinder head and block, became the basis of Miller’s first Indy 500-winning engines in 1922 and 1923. A rule change to mirror Europe’s 1.5-liter Grand Prix engine formula saw Miller downsize the concept and produce the ground-breaking 91 cubic-inch engine penned by Leo Goossen. And with the growing success of the Peugeot-inspired design, Miller began making marine versions for use in speedboats and other sea-going craft.

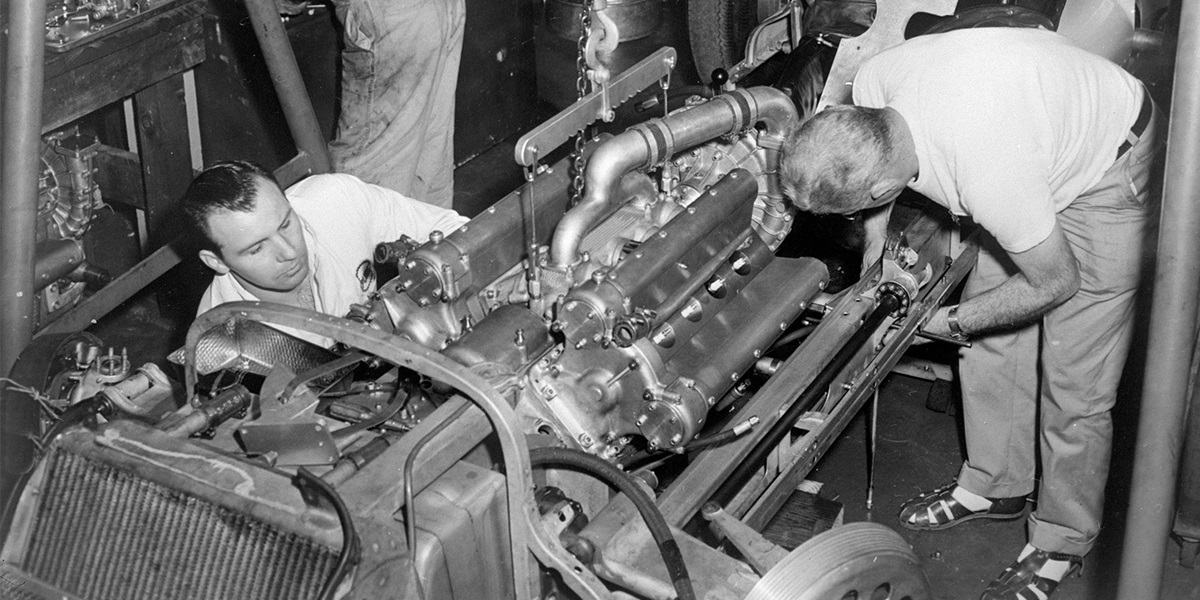

Bankruptcy in 1933 brought an end to Miller’s speed laboratory, and with former employees Offenhauser and Goossen continuing their work at the newly-formed Offenhauser Engineering Company, the four-cylinder Miller marine engine became the basis of the unrivaled “Offy.”

Of all the amazing technological bloodlines at Indy, a thread can be woven from the original 1913-1915 Peugeots to the Millers to the peerless Offys, which won its final “500” in 1976. Under the Offy name alone, the engine earned 27 Indy 500 victories over a 41-year span and scored 18 consecutive wins from 1947 to 1964.

Forever linked through innovation and success, the seven-decade-long imprint on the Indy 500 by Miller, Offenhauser, and Goossen has no equal.

The Offy’s final iteration also helped take turbocharging gasoline-powered engines from its infancy to an idea on the rise in road cars and auto racing. Three cars entered in 1966 Indy 500 used turbocharged Offys, and as the benefits of increased power and fuel efficiency were demonstrated at the Speedway, everyone from auto manufacturers to spark plug companies invested in the nascent technology. By the 1970s, turbos could be found in sedans, sports cars, and all manner of motor vehicles. Formula One even got in on the turbocharging act—11 years after Indy.

Moving from the engine bay, Miller’s contributions extended to drive systems, chassis design and aerodynamics. Whether it was from his shop, or as a brilliant-mind-for-hire after its closure, Miller pioneered the use of streamlined bodies, front-wheel-drive, all-wheel-drive and, remarkably, the first proper rear-engine Indy car—a full 23 years before Jack Brabham’s 1961 debut with the Cooper-Climax. Altogether, six cars and 12 engines bearing Miller’s name won the Indy 500 from 1922 to 1938.

Following 1929’s stock market crash, expensive one-off cars and engines were gradually replaced by roadsters as affordable entries and proven technology took root at the Speedway. Fast forwarding through Indy’s four-year pause during World War II, the “500” resumed in 1946 as older Indy cars, midget-style creations, and gorgeous roadsters from Kurtis Kraft, Watson and others bridged the 1950s and the early 1960s. In yet another Indy 500 first, a six-wheeled entry—the Pat Clancy Special—from 1948 predated the beloved 1976 Tyrrell P34 6-wheeled F1 car by a considerable margin.

If the 1920s served as Indy’s first adventurous decade of race car design, the 1960s could rank as the wildest period for dream-like machines that any series has authored. The first known wing on an Indy car came during practice for the 1962 race when Smokey Yunick fitted a giant airfoil above the cockpit of a Watson roadster. Yunick’s limitless imagination also produced the infamous Indy 500 sidecar in 1964 which was matched for unbridled design adventure in the same year with Mickey Thompson’s low-slung, fendered Sears Allstate Specials.

Taking a page from the 1920s front-wheel-drive Indy cars, Thompson reached back through history and gave front-wheel drive another try in 1965. The ill-handling machine was quickly parked.

Compared to some of the creations Joe Huffaker built from his San Francisco shop, Colin Chapman’s divine, Indy-winning Lotus 38 from 1965 looks positively tame. Huffaker borrowed the liquid suspension concept from British manufacturer MG, fitted the over-sized shocks to his cars in 1964, continued with the damping experiment in 1965, then threw conventional thinking out the window in 1966 when he built two completely different cars using a total of three engines and 16 cylinders!

His twin six-cylinder-engined, four-wheel-drive Porsche-powered chassis was the first (and only) of its kind, and in an effort to embrace sanity, he also constructed the chassis that carried one of the first three turbo Offys. Indy’s unhinged cars kept coming as the STP-Paxton turbine nearly won the “500” on its debut in 1967, more turbines from Carroll Shelby and Lotus appeared in 1968 and by 1969, when the ban on wings was lifted, a new era of technology exploration was born.

Thanks to the first appearance of the “Gurney flap,” Indy’s greatest single year-to-year increase of speed was recorded from 1971 to 1972. All American Racers’ Eagle chassis was responsible for a leap from 1971’s pole average of 178.696 to 1972’s unbelievable 195.940 mph—a 17.2 mph rise—in only 12 months.

Gurney would pass Indy’s aerodynamic baton to Jim Hall, whose Chaparral 2K “Yellow Submarine” employed sophisticated underbody “ground effects” tunnels to dominate the 1980 Indy 500. Thanks to Chaparral, every Indy car built after the 2K uses the same basic design template.

An enduring change took place at Indianapolis in the 1980s as radical engine concepts and homebuilt cars gave way to specialist constructors. The “500” became almost the exclusive domain of chassis builders March, Lola and Penske as past winners struggled to maintain their market share. Advanced manufacturing methods and materials, including the first appearance of carbon-fiber, forged a new standard in the mid-80s, and as Reynard, Dallara, and G-Force joined in the 1990s, rigid, lightweight monocoque technology reached its zenith.

With Indy’s next great chassis concept waiting to be discovered, auto manufacturers continue the tradition of using the “500” as a relevant venue to develop tomorrow’s engine componentry.

Thirty-six of the 40 cars that started the first Indy 500 used naturally-aspirated inline four-cylinder engines that stood a few feet tall, made roughly 100 horsepower and required a small army to lift. To appreciate the evolution from 1911 to 2020, all 33 of the starters in the 104th race will use tiny twin-turbo V6s from Chevy and Honda that can reach 750 hp, rely on fuel-saving direct-injection systems and tip the scales as just over 200 pounds.

In between, we’ve seen flat-6s, inline-6s, inline-8s, V8s, V16s, superchargers, turbos, turbodiesels, non-turbos, stock blocks, engines with the exhausts exiting from the top, exiting from the sides, and even had piston-less powerplants when the turbines whooshed their way around the 2.5-mile oval. Engines from Buick, Cosworth, Offenhauser and select others breached the magical 1,000-horsepower mark, and with 1994’s “Beast” — the Ilmor-built Mercedes-Benz turbo V8 that powered Penske to victory — top speeds surpassing 250 mph also became a reality at the Speedway. With every broken threshold at Indy, technology has been the driving force.

Tire development was present at Indy from the outset and spiked during the transition period from roadsters to rear-engine cars. With the unique ‘drifting’ style of driving demanded by the roadsters, tire engineers sought brand-new levels of performance and durability to reach Victory Lane.

Forty-three straight wins went to Firestone before Goodyear broke the streak in 1967 as the rear-engine revolution took hold and aerodynamics became an increasingly important technology to exploit. The “500’s” great tire wars raged as Goodyear and Firestone poured untold millions into research and development. Cars went faster, used more downforce to corner at elevated speeds, and tire designs grew wider, used lower-profile sidewalls and eventually graduated from grooved treads to full-width slicks to keep pace.

The two brands would use the “500,” and other racing series, to filter massive amounts of data from the track to their road tires. With the graduation from bias-ply to radial construction, Indy once again played a central role to shaping the technology used in everyday life.

Among the most recent frontiers to be crossed at The Brickyard, the proliferation of electronics and computer-based systems has been tied to many advancements. Many cars and trucks sold today come with low tire pressure monitoring devices affixed inside each wheel; the units first appeared at the “500” in the late 1980s and are now considered essential components in driver safety on and off the track.

In concert with the real-time tire pressure systems, onboard data acquisition recorders, live telemetry, and LCD cockpit dashes arrived at the same time as Indy blazed a digital trail.

The modern Indy car, with hundreds of sensors and data channels, sculpted aerodynamics, miniaturized engines, exceptional tires and state-of-the-art driver safety, is a far cry from Harroun’s Marmon “Wasp.” It’s also worth remembering that for its time, the 1911 Indy 500 winner represented the forefront of automotive design and conceptual thinking. Despite the relative age of many Indy cars in the IMS Museum, the majority serve as technological bookmarks in Speedway history.

Outside of Indy’s contributions to the auto industry, The Brickyard has taken safety to new heights with the SAFER Barrier it created in partnership with the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Combined with the infield, life-saving IU Health Emergency Medical Center and the AMR INDYCAR Safety Team, the “500” can boast a legacy of technical excellence that extends well beyond the field of 33.

With more than 100 races to look back on, the last question to ponder is where dreamers and their newfound technology will take the next 100 Indy 500s. Could energy recovery and electrified propulsion systems arrive? Can hydrogen fuel cells or other undiscovered power sources replace the internal combustion engine? Will future Indy cars continue to use wings?

It’s impossible to predict what the next Millers, Chapmans, Gurneys, Halls, or Yunicks will invent, but we know Indianapolis is where they’ll head to test their mettle at the “500.”