Two Indy 500 Wins Launched Milton into Sports Stardom in Roaring 20s

July 24, 2020 | By Bob Gates

Larger-than-life characters during the 1920s captured imaginations with inspiring tales of heroic accomplishment and exhilarating exploits. The public was captivated by Babe Ruth, Bobby Jones, Jack Dempsey, Bill Tilden and Tommy Milton.

Yes, Tommy Milton.

The automobile helped put the roar in the "Roaring Twenties," and people were as infatuated with this exciting new technology as they were with sports. The men who mastered those complicated engineering marvels, while overcoming the life-threatening perils of the racetrack, were idolized and romanticized as "Knights of The Roaring Road.”

Milton was one of the most admired. He was universally extolled for his racing successes, achieved even though he was believed to be blind in one eye. He was a virtuoso on the high-banked, superbly fast, thrillingly dangerous board tracks.

He held the title, "The Fastest Man on Earth." He won the AAA National Championship. And, most significantly, Milton was the first two-time winner of the Indianapolis 500.

In the second decade after its inception, the Indianapolis 500 was already a classic. Considered the most important race in the United States, if not the world, it was a stringent test of a driver's strength, perseverance and ingenuity. To win it once made a career. To win it twice ranked a driver among the immortals.

Possibly distracting, but more likely adding to his mystique, was Milton's relationship with another of the Roaring Road's accomplished knights: 1922 Indianapolis 500 winner Jimmy Murphy.

Murphy, an orphan, became Milton's protégé, and his first racing experience came, literally, at Milton's elbow. Murphy acted as his riding mechanic in many races, including Milton's victory during the prestigious 1919 Elgin Road Race.

Milton provided Murphy with his first driving opportunity as a co-driver on the Duesenberg team. And Milton got Murphy reinstated after Fred Duesenberg bumped him back to riding mechanic because of too often crashing. Milton watched after Murphy. Took care of him.

By 1920, Murphy had rewarded Milton's confidence with victories and was given the responsibility to help prepare Milton's custom-built Duesenberg for a land speed record attempt in April at Daytona Beach, Florida.

While Milton was in route to Florida from a race in Havana, Fred Duesenberg asked Murphy to test the car. Murphy obliged and inadvertently exceeded Ralph de Palma's record.

The run was not officially timed and did not stand as a record. But upon his arrival, Milton faced headlines proclaiming Murphy's speed and questioning whether Milton could top Murphy's astounding accomplishment.

Milton did later claim the land speed record, but he was furious at Duesenberg and Murphy for the high-speed test. He had invested much of his own money and innovations in the car and felt a sense of betrayal.

Milton left the Duesenberg team, and his friendship with Murphy became strained. The result was not the blood feud trumped up in the sensationalist press of that day, but their friendship was not the same.

Milton never forgave Murphy for the incident in Daytona Beach, always believing that the opportunity to break the record, "...overrode his evaluation of loyalty toward me."

"I don't think the world ever looked so black as on that day," the usually private Milton revealed to writer Griffith Borgeson. "I could've killed him. The incident resulted in practically a total breach between Murphy and myself. Breaking the record gave me the satisfaction of beating both de Palma and Murphy."

There are those who contend, however, that Murphy was an innocent bystander in the situation.

Milton's desire to continually best Murphy was played out on tracks across the country, particularly at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. Milton succeeded there first, winning the 1921 “500” with a telling demonstration of his relentless resolve and innate intelligence as a driver.

After leaving the powerhouse Duesenberg team, Milton joined the Chevrolet brothers and their effort in 1921. Toward the race’s end, he'd worked one of their Frontenacs into the lead but was in jeopardy of losing it to the faster Roscoe Sarles, who was gaining quickly in a Duesenberg.

Desperate, Milton resorted to a bit of psychology. He deliberately allowed Sarles a passing attempt. When Sarles made his move, Milton accelerated, looked over at Sarles with a beaming smile, and patted the tail of his car as if saying, "I'm feeling great, how about you?"

The exhausted Sarles, not wanting to risk an accident while battling the seemingly fresher Milton, slowed and settled for second place.

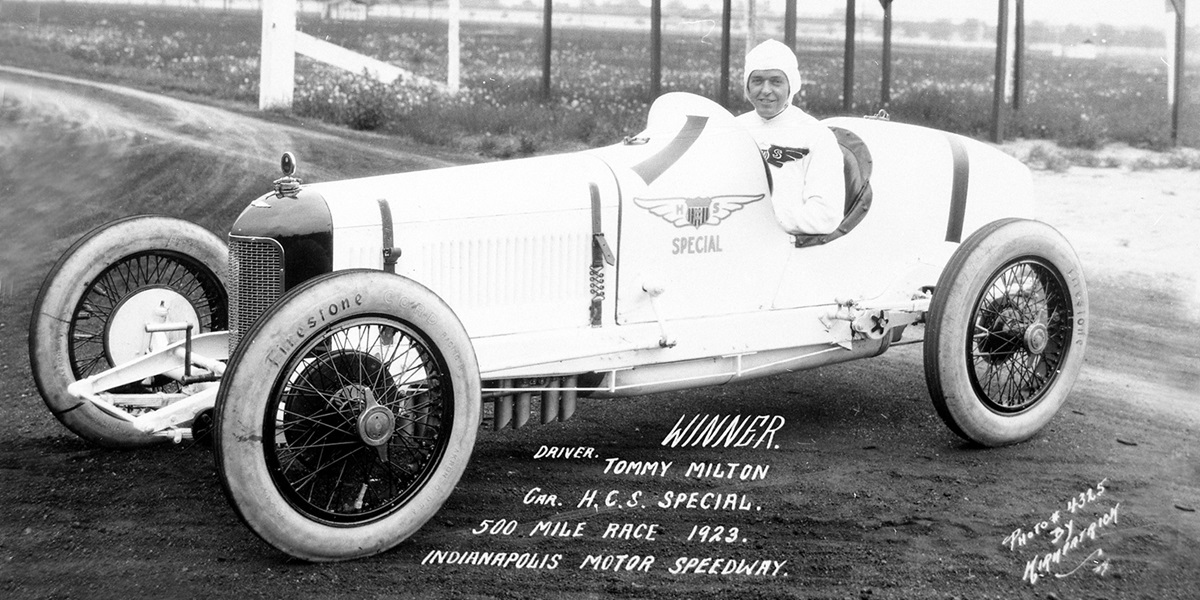

In 1922, Murphy matched Milton's Indianapolis 500 win with his victory. Not to be outdone, in 1923 Milton made history by repeating as an Indianapolis winner.

Driving a Miller owned by Harry C. Stutz, Milton dominated. He won the pole, exceeding the track record by an incredible 7 mph, and after repelling an early challenge from Murphy, he led for much of the race on his way to the win.

That intensified the media frenzy surrounding Milton and Murphy's rivalry, with speculation running rampant about how it might be resolved on the bricks at Indianapolis in 1924.

The following year, both left disappointed. Milton fell out early, and Murphy finished a distant third.

A much anticipated Indianapolis rematch in 1925, tragically, never materialized. Murphy was killed in a crash Sept. 15, 1924 at a dirt track race in Syracuse, New York.

Distraught, Milton, took charge. The two men may have had their differences on the track, but at the end of the day, they were friends who looked after each other. Aside from an uncle that helped raise him, Murphy had no father figure in his life, and Milton filled that void and showed him the path to a successful life.

Taking care of his former friend in death as he had in life, Milton signed Murphy's death certificate, and per the request of Murphy’s uncle, accompanied his body on the solemn train ride back to his California home.

Milton last raced at Indianapolis in 1927, but he remained an important part of the Speedway. He initiated the tradition of the Indianapolis 500 winner receiving the Pace Car, when, as a Packard Car Company engineer and Pace Car driver, he suggested the award in 1936.

At the personal request of track president Wilbur Shaw, Milton served as the Indianapolis 500's chief steward from 1949 through 1952, adding credibility to the position and establishing an invaluable rapport between the Speedway management, the AAA and the competitors.

Until his death in 1962, this iconic Indianapolis champion graciously represented his beloved sport, like the shining "Knight of The Roaring Road" he was so often declared to be.