'Rainbow Warriors' Helped Gordon Make History At Brickyard

July 19, 2011 | By Jan Shaffer

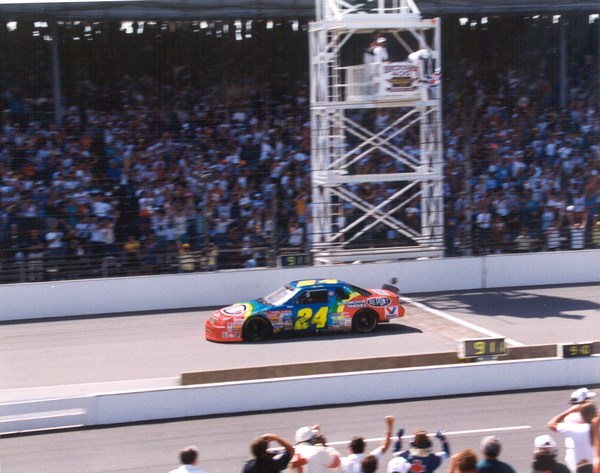

The year was 1994, and it was a historic day at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, with NASCAR’s premier series venturing onto the 2 ½-mile oval for the inaugural Brickyard 400.

There was Pittsboro, Ind., resident Jeff Gordon as the hometown favorite in the No. 24 DuPont Chevrolet, a car with a rainbow painted on the hood. There also was the rest of NASCAR’s finest, plus a few Indy car drivers giving it a try.

Pit crews were starting to be recognized as playing an important part in winning. Spots were gained and lost in the pits. Indeed, Colin Chapman of Lotus, as early as 1965, recruited NASCAR’s legendary Wood Brothers to pit Jimmy Clark and Bobby Johns in the Indianapolis 500, trying to get an edge.

Ray Evernham, who later became a car owner and TV broadcaster, was the crew chief for Gordon in the inaugural Brickyard 400. He had what proved to be a revolutionary approach to the artistry of a pit stop.

“Ray restructured a lot of NASCAR about pit stops,” said George Stephens, the Hendrick team’s assistant general manager who served as the gasman for Gordon’s crew on Race Day. “We practiced twice a week. We did drills and training.”

From inside the team’s ranks came Shawn Parker (tire changer), Charlie Siegars (catch can) and a crewman who would gain future fame as a five-time Cup champion crew chief, Chad Knaus, a tire changer.

Outside “gunfighters” who flew in on race morning and home that night were Mike Trower, the front tire changer who is a project manager for Duke Energy in “real life;” Barry Muse, the jackman who now operates Hillbilly Bob’s Root Beer; and Darren Jolly, the tire carrier who is a driver for UPS.

Together, this band of crewmen became known, from the paint job on the hood and performance, as the “Rainbow Warriors.” They propelled Gordon to victory in the first Brickyard 400 and gained a name for themselves by gaining the title of fastest pit crew later in the year in the series’ contest at Rockingham, N.C.

“We had a really good crew back then,” Knaus said. “We were a little ahead of our time. In that era, we were doing 16-second pit stops, which wouldn’t hold a candle today, but it was pretty good back then.”

The first Indianapolis visit for a NASCAR Cup race was the same remembered experience for crewmen as it was for drivers.

“It was definitely different,” Trower said. “The whole ‘tunnel’ feeling (with seating on both sides) ... it wouldn’t bother you, but you were amazed by it. It gave you the feeling of a historic place. It kind of gives you chills when you go into the place.”

Knaus said: “I had never been to Indianapolis until we went for the test. The thing I respected most was the cars (in the Museum). You look at the Indianapolis 500 team bosses, the manufacturers who have competed there, it was awe-inspiring, whether it was with a turbine or four-wheel drive or whatever.

“When I tell my crew stories of winning the first race there, they’re in a little more awe. I still have the ring.”

Every member of the Rainbow Warriors credited Evernham with masterminding the plan.

“Ray was very organized and put a lot into the pit crew,” Jolly said. “Ray changed the way we did things. Back then, we practiced more than most teams, watched video on our footwork, did sprints, worked in a weight room, went up and down steps. Each individual crewman had something to do if the car was involved in a wreck, a specific duty.”

Stephens said: “Ray’s thinking was so far in advance that it took us to a different level. Ray took athletes and made them pit crewmen and took pit crewmen and made them athletes.”

Indeed, Stephens was a middle linebacker at Northeastern University. Muse was involved in track. Jolly was a second baseman for a season at UNC-Charlotte. Trower’s father was running dirt stock cars before he was born, and he grew up working on cars in northeastern Iowa.

“At that time, I carried two tires,” Jolly said. “You had to be pretty agile, jumping over hoses and things.”

For the inaugural Brickyard 400, the Rainbow Warriors were prepared. Stephens described the scene.

“That was my first visit there,” he said. “To see 100,000 people on the front stretch from Turn 1 all the way to Turn 4 … you could just feel the history, like old Yankee Stadium or Fenway Park. At that time, we didn’t know we were going to be part of history.”

Trower said: “At our team meeting, I remember Ray telling us we were going to win this race. That was my very first time being to Indianapolis. It’s something you would never forget, knowing you would have a chance to win. We’d only won one race at the time (the Coca-Cola 600 at Charlotte).”

Jolly said: “Ray told everybody to be calm and focus on your job. We had a good day on pit road. At the end, it was going to take a good pit stop, and we got one.”

When the checkered flag fell, Gordon was first across the finish line to start a new chapter in the lore of the Speedway, one that is remembered vividly 17 years later by those who were a part of it.

“That was my most memorable moment, as exciting as it was that day,” Stephens said. “Of all the championship rings I have, the Brickyard is my favorite, my most memorable.”

***

2011 Brickyard 400 tickets: Tickets are on sale for the 2011 Brickyard 400 on Sunday, July 31 at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway.

Race Day ticket prices start at just $30. Fans can buy tickets online at www.imstix.com, by calling the IMS ticket office at (317) 492-6700, or (800) 822-INDY outside the Indianapolis area, or by visiting the ticket office at the IMS Administration Building at the corner of Georgetown Road and 16th Street between 8 a.m.-5 p.m. (ET) Monday-Friday.

Children 12 and under will receive free general admission to any IMS event in 2011 when accompanied by an adult general admission ticket holder.

Tickets for groups of 20 or more also are on sale. Contact the IMS Group Sales Department at (866) 221-8775 for more information.