Parnelli Delivered on Herk’s Promise with Magic Pole Run in 1962

July 27, 2020 | By Steve Shunck

"You think that was something?" Jim Hurtubise said with an ear-to-ear grin after his record-setting run on the fourth day of qualifying for the 1960 Indianapolis 500. "Wait ‘til next year, when my friend Parnelli Jones gets here!"

Herk had just shattered the IMS track standard with one- and four-lap records, powering to a quick lap of 149.601 mph.

With seeming ease, Hurtubise had erased Eddie Sachs' qualifying mark by an unthinkable 2.5 mph, with a four-lap average of 149.056 mph, edging ever so close to the much-sought, once-thought-improbable, 150-mph average for the storied 2.5-mile Brickyard. Hurtubise had established his record runs during the third day of qualifying, and thus was ineligible for the 1960 pole position.

The 150-mph barrier definitely was within reach of the Indianapolis racing fraternity. But the drivers would have to wait two more years, until 1962, for the mark to fall, with Herk's best friend, Jones, inking his name in the all-time Indianapolis record books.

Following the 1960 race, many railbirds thought the 150-mph mark would be shattered in 1961, the Golden Anniversary of the "500," but it wasn't to be. Eddie Sachs captured his second straight pole with a speed slightly quicker than his pole run the year before but nowhere close to the one- and four-lap marks Hurtubise set in 1960.

Sachs topped his 1960 pole speed of 146.592 mph by less than 1 mph, with a four-lap average of 147.481 mph. The hero, standard-setter and prognosticator from the previous year, Hurtubise, had a very respectable qualifying run of 146.306 mph to start on the outside of the front row.

Herk's pal, and the driver he had told the racing world to watch the previous May, 1960 USAC Midwest Sprint Car Champion and 1961 Indy 500 rookie Jones, qualified for his first “500” at 146.080 mph in the No. 98 Agajanian Willard Battery Special, earning him a spot in the middle of the second row.

In the race, Jones lived up the accolades bestowed upon him, leading 27 laps before losing a cylinder around the 200-mile mark. For the remainder of the race, Jones drove his dying Offenhauser-powered Watson roadster with a gash above his right eye, caused by a piece of metal that had been sucked off the track and struck him just above his goggles, causing a bloody mess and a swollen eye.

"Losing the cylinder was biggest downfall that day for me, not the cut on my forehead," Jones said. "I was really down and out the whole rest of the race, because I knew I had a great chance to win or run up front, and then all of it went away just like that when I lost the cylinder. It was really disheartening to me because I had a lot of desire to win. That was my attitude."

A.J. Foyt outdueled and outlasted Sachs in the Golden Anniversary “500” to win the race, while Jones came home in 12th place, completing 192 laps despite myriad difficulties. He would also earn co-Rookie of the Year honors with friend Bobby Marshman, who charged from 33rd (last) on the grid to finish seventh.

"Later in 1961, after the ‘500,’ I got to do a lot of the tire testing for Firestone, and I perfected what I started to learn in 1960 testing,” Jones said. “I could slip the car sideways through the corner. If I pitched the car into the corner and got sideways and snapped it around and caught it in time, it would take the bind out of the car and I'd come off the corner much, much faster, and the lap speeds increased.

“Harvey Firestone Jr. would bring his son out the track, and I used to see how far sideways I could slide the car for him while he took photos as I drove though the corners. At times, I almost overdid it to show off for him, but it taught me a new, quicker way around the Speedway."

And Jones was quicker when the track opened in 1962.

Almost immediately, he flirted with the coveted milestone of 150 mph. But the blue-eyed, soft-spoken Jones never topped the barrier leading up to qualifying on Saturday, May 12.

On nearly every practice day leading up to the pressure-packed Pole Day – when a crowd estimated at 150,000 eagerly anticipated Jones' run at the record in the No. 98 Watson Roadster – he had consistently clocked speeds in the 148- to 149-mph range, with a top speed just an eyelash away from the coveted mark: 149.7 mph.

Another contributing factor to the increased speeds in 1962 was the fresh asphalt that covered the entire front stretch and left only a ceremonial Yard of Bricks exposed to the drivers and fans. Most of the stretch became smoother and faster, matching the paved surface around the 2.5-mile oval for the first time in the history of the Speedway.

"The brick surface was like driving on ice," said Jim Rathmann, winner of the 1960 race. "You would point the car toward Turn 1 when you came out of Turn 4 and hang on for dear life and hear the car go ‘thud, thud, thud’ as it bounced over the bricks. The front tires had no grip. Wow! That was scary and a handful for all of us."

Even with a smooth, fast track and a month of near-record speeds, there were still skeptics that a time of one minute flat around the 2.5-mile track was something a front-engine roadster could achieve, no matter what the driver’s skill level was, prior to the 1962 running of the “500.”

"I remember Pole Day was pretty windy and hot, in the 90s, during final practice before qualifying,” Jones said. “We were running right at 150 or a little over in that morning practice session, and I was fairly confident I could run 150 during my qualifying run and put four good laps together. We’d been quick the whole month and run nearly 150, but we weren't quite there.

“With the straight paved, it sure made qualifying easier than the year before when it was brick. Qualifying is about being smooth and consistent; the year before I tried to overdrive the car at times. In 1962, with all the practice from the year before and during the month, I learned how to be smooth and get the car through the corners.

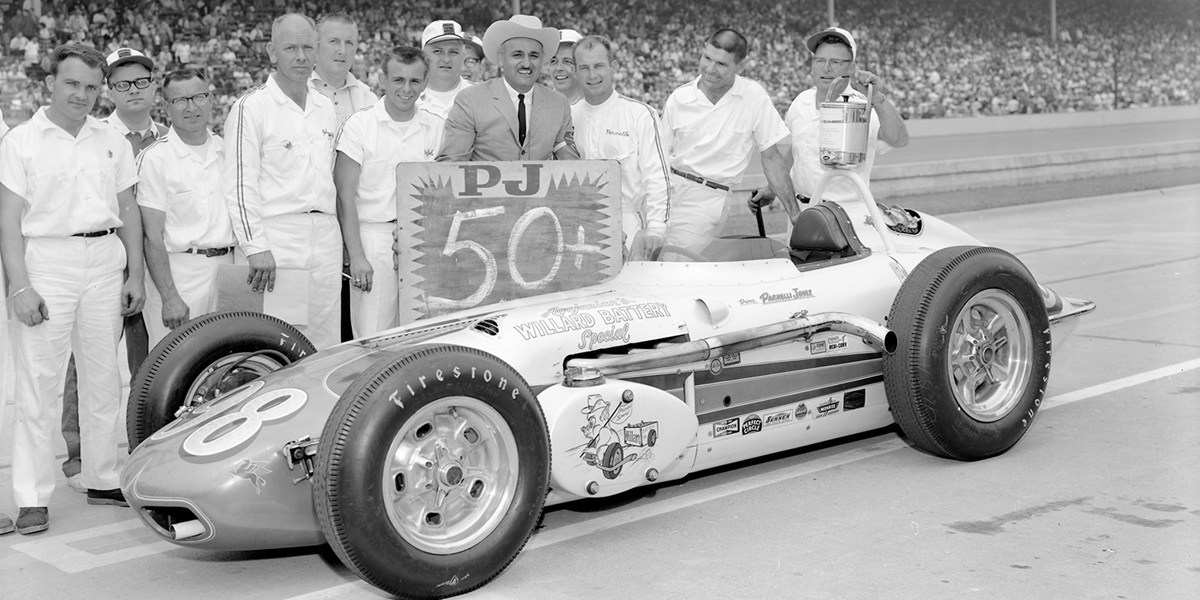

“I remember going by my pit board on each lap of qualifying and seeing ‘50+’ on the board, so at that point, I knew if I was smooth on each lap, I’d break 150 on the run. There were a lot of people watching in the stands that day, and they all wanted to see someone set the mark. When I pulled in after the run, it was a big thrill. Indianapolis really carried a lot of prestige.

“Before we posed for photos, Phil Hedbeck (an Indianapolis Bryant Heating and Cooling distributor) had me put my helmet up, and he emptied 150 shiny silver dollars into my helmet. It was a great thrill. I was in awe with the whole thing, obviously. Aggie (car owner J.C. Agajanian) and the crew guys were all so happy, shouting and jumping all over the place. Everyone had worked so hard, and the photo with the ‘PJ’ pit board and ‘50+’ pretty much tells the story of the success we had in qualifying.”

Jones had achieved the elusive record of a 150-mph four-lap average with a flawlessly smooth, methodical run, ticking off the four pressure-filled 2.5-mile laps through four turns using bravery, skill and unthinkable talent.

The lap-by-lap breakdown:

May 12, 1962

Lap 1 - 59.71 seconds, 150.729 mph

Lap 2 - 59.94 seconds, 150.150 mph

Lap 3 - 59.89 seconds, 150.276 mph

Lap 4 - 59.87 seconds, 150.326 mph

Total elapsed time - 3:59.41.

Average speed - 150.370 mph

He had driven his tested-and-true roadster, nicknamed "Calhoun" – which first turned a lap at the Speedway in 1960 with Lloyd Ruby – to a record that remains one of the most revered in the history of the storied Brickyard. So historic, in fact, that when Jones' competitors showed up at Indy in 1963 they were forced to endure a month of wearing silver pit badges depicting his 1962 pole-winning car!

“When Herk was on the public address system after he qualified in 1960 and everyone at the track and the media could hear him, and he said: 'Well, that ain't nothing. Wait till Parnelli gets here.' That made me feel great, long before I ever turned a wheel in the race or qualifying at Indy,” Jones said. “But it also meant that when I got here, I needed to perform."

Perform he did, achieving the record mark in only his sophomore year at the track.

A.J. Foyt, one of Parnelli's fiercest rivals and best friends, would have to wait until 1963, like every other driver at Indianapolis Motor Speedway, to join the 150-mph fraternity of which Jones' was the sole member.

"Naturally, since I couldn’t break the 150-mph barrier at Indianapolis, I was glad to see Parnelli break it, ‘cause we raced midgets and sprint cars together before Indy,” Foyt said. “We raced hard against each other, so I was just glad a good friend of mine was the first one to break the barrier. It seemed simple, but it was so hard to run 150 back then. It was a hell of a run in those days; a hell of a run."