Brickyard’s Prestige Soared after Wright Brothers’ Flights in 1910

June 17, 2020 | By Mark Dill

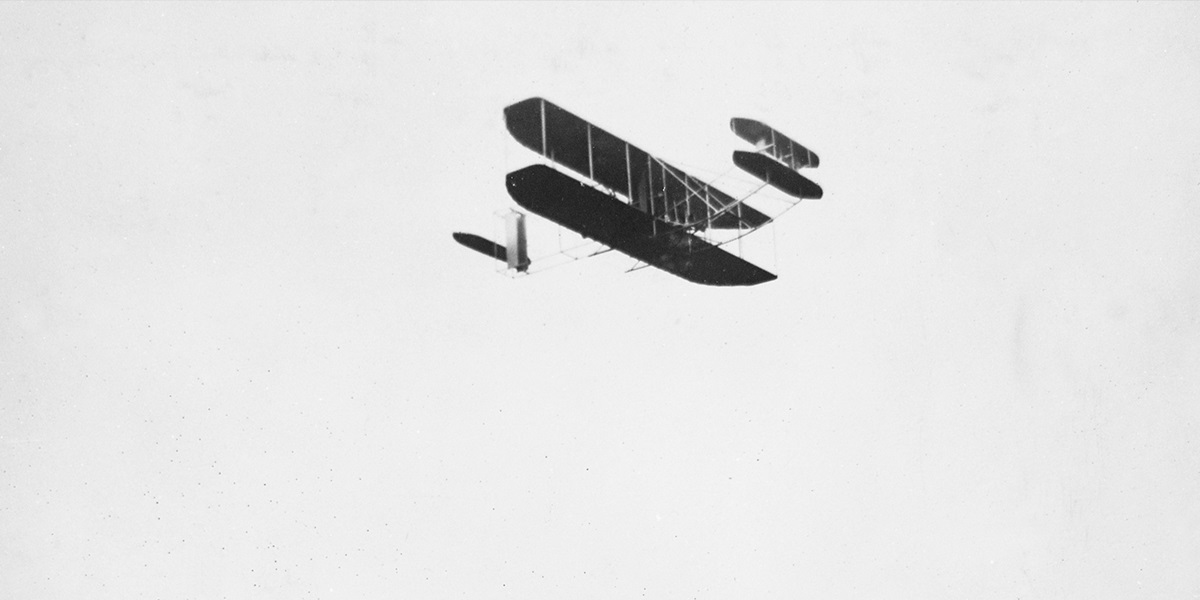

Perhaps the best example of how the founding fathers of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway saw their facility as something more than a racetrack was the aviation show they staged from June 13-18, 1910. Just seven years after their first flight on the Outer Banks of North Carolina, Orville and Wilbur Wright brought their latest-generation biplanes to The Brickyard for a thrilling display of the latest form of transportation.

Speedway founders Carl Fisher, James Allison, Arthur Newby and Frank Wheeler were more than “car guys.” They were entrepreneurs fascinated by technology and its business potential. In 1910, airplanes were a marvel, and most people in Indianapolis had never seen one mount to the sky.

In preparing for the Speedway’s first full year of operation in 1910, management organized the first licensed aviation meet in America. This was also the first public demonstration of airplanes in Indiana. The track was closest thing to an airport in the state – maybe the country.

The Speedway was transformed with the erection of an infield “aerodrome” to house planes. At its entrance was a wooden “monorail,” a guide with a groove cut in it to launch planes because they used skid pads, not wheels. American flags marked a course in the infield so judges could assess how well pilots stayed within its parameters as they did “laps.”

Two of Wilbur and Orville Wright’s planes arrived by train on Tuesday, June 7. Of 11 entries, the Wrights owned six. Four planes were entered by Indianapolis-based aviators Joseph Curzon, Mel Marquette, Russell Shaw and George Bumbaugh. Bumbaugh, who taught Carl Fisher how to fly a gas balloon, was entered in a plane owned by Fisher, a Fisher-Indianapolis. A single monoplane was entered by pioneer aviator Lincoln Beachey. Only the Wright planes would get off the ground.

In addition to Orville Wright, the pilots of the Wright entries were Al Welsh, Frank Coffyn, Arch Hoxsey, Ralph Johnstone, Duval La Chappelle and Walter Brookins. Hoxsey and Johnstone would perish in airplane crashes before the end of the year.

Orville Wright opened the meet Monday, June 13 when he slid his flyer along the wooden monorail and ascended into the sky shortly before noon. He flew away from the aerodrome, which was located near the inside of Turn 2 of the track. Eventually ascending to an altitude of about 125 feet, Wright flew above the track, tracing its outline for two laps and then gently landed back near the aerodrome.

Most of the Wright pilots took to the air with judges timing them for “laps” of the track. Brookins stole the show. The Wright’s 21-year-old star had only taken up flying three months prior. All the more astounding was his daring flight on the 40-foot wingspan plane made of balloon silk stretched over a spruce wood frame as he snatched a new world’s altitude record at 4,384.5 feet. The old record of 4,165 feet by Frenchman Louis Paulhan was 5 months old.

A modest crowd of about 2,000 witnessed a spectacle that would be amazing today, that of a person soaring so high in such a fragile-looking contraption. Equally impressive, the risk-taking Speedway President Fisher gladly accepted Orville Wright’s offer to become one a handful of people in the world to fly as a passenger.

Humbled, Fisher confessed to a white-knuckle experience during his 10-minute flight.

“I’ve had enough,” Fisher said. “If there are no dents in the framework where I had it gripped, it is because I couldn’t squeeze hard enough.”

Fisher’s plane, flown by Bumbaugh, fared worse. The machine crashed to the ground on an attempted take-off. Bumbaugh was shaken up but suffered no major injuries.

The next two days were hampered by winds and rain. Speedway management flew signal flags, such as one that communicated “may fly later,” to let spectators know the status of the program. With planes more temperamental than race cars, officials offered “wind checks” as well as traditional rain checks to insure customers.

While some flights did occur, the original programs were shortened. On Tuesday, spectators received a special treat when one of the Wright flyers was stationed on the front stretch and people were allowed to surround it.

Wednesday’s weather was worse, and the Wright pilots ventured upward only a few hundred feet. Late in the day, winds calmed and Orville Wright took to the air during dusk. He returned with a romantic account of soaring to 2,000 feet and peering over the horizon to spy the sun after dark.

Thursday saw a match race between Brookins and a “half-breed” car called the Overland Motor Company Wind Wagon. The two had also raced Tuesday, with Brookins credited with winning.

Overland, an Indianapolis manufacturer, fashioned the novelty car. Its engine powered an 8-foot wood propeller at the rear, mounted on a chain-driven shaft and positioned high to clear the ground. Brookins was again credited with beating the car, driven by Overland test driver Carl Baumhofer, in the one-lap chase. Baumhofer recorded the lap at 60 mph.

Later Brookins put on a dazzling display of air acrobatics. Twisting his cloth-winged flyer in mid-air at 82 degrees, the young pilot had fellow aviators in awe. Timed by Orville Wright, Brookins spun the plane a full revolution in 6.4 seconds. Both Wright brothers ran to their student when he touched ground, excitedly shaking his hand.

When asked if Brookins would attempt the daring maneuver again, Wilbur Wright said: “Never again with my consent. I don’t think he or anyone could do it again and get away with it.”

Hoxsey thrilled the gathering a different way. His engine stalled as he circled the track and he glided out of sight to a field southeast of the Speedway, scattering cows and horses as he touched down unharmed.

Friday’s big event was the highlight of the week – another world’s altitude record by Brookins. In another dusk-time flight, Brookins wasted no time in climbing to high altitude. After ground engineers measured his height at 4,938 feet, the plane disappeared from the sight of Speedway onlookers.

Like Hoxsey before him, officials and spectators alike feared the worst, but he had glided to safety. Those first to his side found him sitting on his flyer smoking a cigarette. The wooden monorail was moved to his landing spot and he opened the final day of the event Saturday by making the grand entrance of flying into the Speedway.

Saturday proved anticlimactic with one exception. After the planes of his other pilots were stored in the aerodrome, Orville Wright mounted the skies to close the meet just as he had opened it. As Wright pirouetted in the air with exceptional skill, the handful of spectators remaining marveled at the spectacle.

The legendary Wright’s masterful command of the amazing new aircraft brought a fitting conclusion to an event hosted by the legendary track founded as a technology proving ground. While the crowds approached 20,000 in the closing days, they frequently dwindled to a few hundred as gusty winds hampered the fragile craft. The event became a brief chapter in Speedway lore, never to be repeated.