From 'Sneaking In' to a Seat in the Pagoda, PennGrade's Miller Takes Emotional Journey to 100th Running

May 26, 2016 | By Phillip B. Wilson

In the early morning hours of May 30, 1969, a father and his 15-year-old daughter drove through a north Indianapolis Motor Speedway gate and parked a 1966 blue Ford Falcon in the dark.

Luis Alvarez was reporting for work as a groundskeeper at 3 a.m. Gisela Alvarez slept on blankets in the back seat until race fans were allowed in the gates for the 53rd Indianapolis 500.

They had arrived from Cuba a few months earlier. Neither father nor daughter spoke English.

“I don’t think I was supposed to be in the car,” said Gisela (Alvarez) Miller. “He was sneaking me in.”

They didn’t see the race. They heard it from the infield.

“It was way too loud. I had never heard anything like that,” Miller said. “I had never seen that many people in my life. I didn’t think there were that many people in Cuba.

“Mario Andretti won. I thought Mario Andretti had a nice name, but that was about it.”

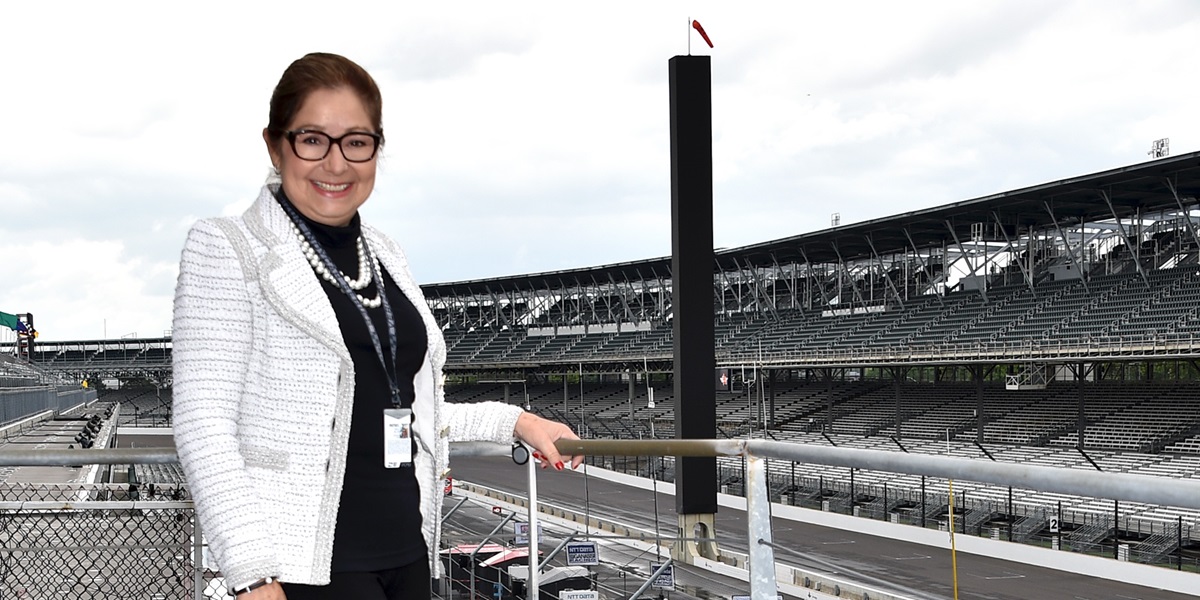

Miller, 62, laughs at her ignorance now while sitting on the third floor of the Panasonic Pagoda during a recent practice for the 100th Running of the Indianapolis 500 presented by PennGrade Motor Oil.

Her life journey is a script Hollywood might dismiss as unrealistic. This girl who didn’t have a clue about the country, let alone “The Greatest Spectacle in Racing,” eventually rose through the business ranks to become president of D-A Lubricant Company, which is launching PennGrade Motor Oil through its sponsorship of the “500.”

That girl who used to sneak on the grounds is now an IMS VIP at the heart of the track her father loved thanks to her Lebanon, Indiana, company’s sponsorship of Sunday’s race.

“This is special,” she said.

Luis and Maria Alvarez wanted to give Gisela a chance at a successful life. Her father was a CPA with a successful accounting business in Cuba, but her parents gave up everything they had to flee the Communist country when Fidel Castro came to power. As Spanish citizens, they were permitted to leave.

“They did it for me,” she said. “When I came to this country, I didn’t even know what gum was.”

Aside from not knowing the language, they had basically nothing. Luis eventually landed two jobs, at IMS during the day and RCA at night. Maria became an electronics assembler. Gisela made extra money cleaning homes, starting with the apartment of their next-door neighbor, a prostitute.

“We lived in a one-bedroom apartment,” she said. “I slept on the floor for three years until we could afford to get a two-bedroom apartment.”

On weekend evenings, the Alvarez family visited a Burger Chef to search through the trash for throw-away food. Two or three edible buns qualified as a worthwhile search.

“It was like we were homeless,” she said.

That first “awesome” visit to hear the Indy 500 included lunches with bologna sandwiches, chips, grapes and water “because we couldn’t afford pop.”

Father and daughter couldn’t have been more hooked.

“I wanted to come back,” Miller said. “I thought they had these races every other week. I mean, my father worked here year-round, right? (Laughs.) What does he do the rest of the time? (Still laughing.)”

When in high school, she was allowed to walk the infield and check out the famed “Snake Pit” party area. Her father kept an eye on her with hourly patrols, so she didn’t fall in with the wrong crowd.

Miller eventually saw the Indy 500 when her father’s friendships with “Yellow Shirt” Safety Patrol personnel provided a view. In 1984, Luis bought his first tickets, in the Southwest Vista.

“This is all he knew. He loved being here.” she said. “He would glow when he brought people over here. It was like he owned the damn place, you know?”

Luis wanted his daughter to be a secretary, then hoped she’d become a dental hygienist. She went to the University of Indianapolis and earned undergraduate and graduate degrees, then entered the business world. She moved up the corporate ladder quickly, eventually joining D-A as a financial analyst in 1984. After various jobs within the company in customer service and special projects, she became its first female director. A change in ownership led to her promotion to chief financial officer. She became president in 2008.

Her racing connection began with the Rahal Letterman Lanigan team. D-A was a primary sponsor on Graham Rahal’s No. 15 car for a race last year. Mike Lanigan had a pair of yellow Chuck Taylor tennis shoes made for Gisela with a team logo on one heel and a D-A emblem on the other. She says they’re her “good luck shoes.” She’s since added a pair of red-and-black sneakers with the same design.

“This is our second year with D-A and she’s been a big supporter from day one,” said Bobby Rahal, the 1986 Indy 500 winner. “For us, it’s been a really good relationship and I think we’ve brought them some business. It’s been a good partnership. She’s helped us and we’ve helped them.”

Miller has grown into the most passionate of race fans. She wears the black-and-white colors of a checkered flag for the Month of May. She has the pleasure of walking out onto the terrace of the Panasonic Pagoda’s third floor, the cars zooming by that platform with sound and fury. She immerses herself in that atmosphere, as if letting it wash all over her.

“It’s pretty amazing, where she is today compared to where she was when she came to this country,” said Ron Miller, her husband of 38 years. “You can’t make this stuff up.”

Inevitably, when taking in that picturesque Speedway view of the front straight, she thinks about her parents. Luis died in 2000 and her mom the next year.

Miller envisions what it will be like on Sunday, when 33 cars come off that fourth turn and speed toward the Yard of Bricks start/finish line. She gets tears in her eyes thinking about it.

“If only my father were alive,” she has said repeatedly to so many family and friends. “He’d be crying. He’d be so emotional, the happiness the pride.”

Miller will revel in that moment.

“This became my father’s life,” she said. “I will definitely be emotional.”